The Ongoing Horrors of Kissinger's Explosive Legacy in Southeast Asia

Decades after Henry Kissinger's influential role in Southeast Asia, the region still grapples with the lasting impact of his military campaigns and bombings Explore the ongoing casualties and disputed legacy left behind

Henry Kissinger's impact on American foreign policy in Southeast Asia still lingers fifty years later. The remnants of the bombing and military campaigns he supported continue to pose a threat in the region. In Cambodia, unexploded ordnance from Vietnam War-era carpet bombings, orchestrated by Kissinger and President Richard Nixon, continue to kill and maim adults and children, year after year.

The 17 million strong country is still in the process of recovery from the Khmer Rouge genocide, where experts believe that the brutal and overthrown government was able to gain recruits due to the desperation caused by continuous American assaults.

"(Before the Americans) the Cambodian countryside had never been bombed out ... but (then) something would drop from the sky without warning and suddenly ... explode the entire village," stated Youk Chhang, who serves as the executive director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia located in Phnom Penh.

"After experiencing the devastation of having his own village bombed and losing his siblings and parents due to American bombs, Chhang, a survivor of the Khmer Rouge's brutal regime, posed the question: should one choose to be a victim and succumb to the bomb, or fight back? His organization now aims to document the horrors of the genocidal regime. Chhang noted that even today, the generation born after the Khmer Rouge may not be familiar with the names or legacy of Kissinger and Nixon, but they are well aware of the history of B52 bombers and the American involvement in Cambodia."

The passing of Kissinger at the age of 100 last week has brought renewed attention to the controversial figure's actions in American diplomacy. Critiques have been particularly pointed in Southeast Asia, where the US was already engaged in war when Nixon assumed office in 1969.

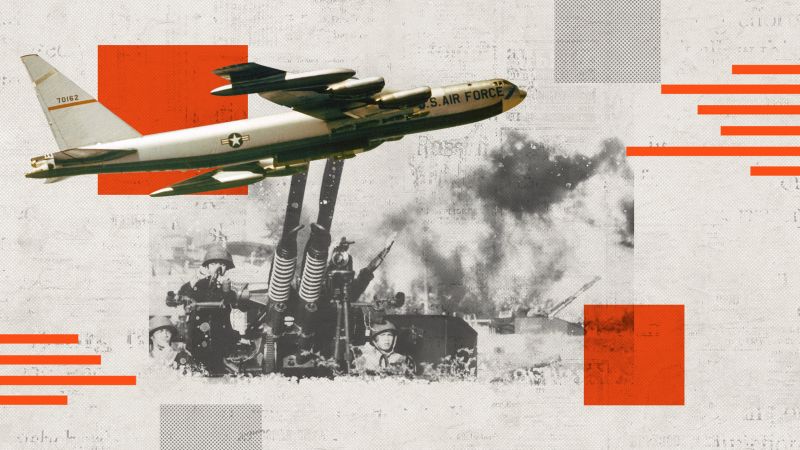

Kissinger, who held the positions of national security advisor and later secretary of state, received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973 for his efforts in negotiating a ceasefire that marked the end of US participation in the Vietnam War. This recognition followed a period of intense US bombing in northern Vietnam.

Declassified documents from recent decades have revealed the true extent of the closed-door decisions made by Kissinger and Nixon. They authorized covert bombings in Cambodia and extended a secret war in Laos in an effort to cut off North Vietnamese supply lines and suppress Communist movements in the region.

The death toll during this time in officially neutral Cambodia and Laos is unknown, but historians believe it could exceed 150,000 in Cambodia alone.

Analysts have also uncovered the role of Gerald Ford and Kissinger in conveying America's support for Indonesian President Suharto's bloody 1975 invasion of East Timor, which is estimated to have resulted in at least 100,000 deaths.

"Kissinger and Nixon viewed the world in terms of achieving their desired outcomes - those in weaker or marginalized positions were of little importance to them. The fact that they were unwilling pawns, essentially becoming cannon fodder, held no significance," said political scientist Chong Ja Ian, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore.

Casualties continue

"This type of behavior comes with a broader cost for the US - much of the ongoing doubt and distrust towards the US and its motives stems from actions like those carried out by Kissinger and Nixon."

Between October 1965 and August 1973, the United States released over 2,756,941 tons of ordnance over Cambodia, a country about the size of the US state of Missouri. This surpasses the amount dropped by the Allies during World War II, as reported by Yale University historian Ben Kiernan. The leftover ordnance in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, along with landmines and other explosives from subsequent years of conflict in the region, still present a serious threat to the people living there.

vietnam-war-us-b52-illo

US airman reflects on the trauma of the Vietnam Christmas bombings 50 years later, comparing it to walking on missiles. In Cambodia, nearly 20,000 people have been killed by mines and unexploded ordnance between 1979 and this past August, with more than 65,000 injured or killed since 1979, according to government data. The majority of casualties are from landmines, but over a fifth are victims of other types of leftover explosives, including those from American campaigns, experts report.

In the first eight months of this year, government data shows that explosives led to the deaths of four people, injuries to 14, and the need for amputations for 8 individuals. The impact of these incidents, particularly in rural areas, is expected to be felt for many years to come, according to experts.

"Twenty to thirty percent of all fired and dropped explosives fail to detonate... We will likely be contending with these hazards here for the next 100 years. This is Kissinger's legacy," commented Bill Morse, president of the nonprofit Landmine Relief Fund, which provides assistance to organizations such as Cambodia Self-Help Demining.

The group not only works to safely handle explosives but also educates people on how to recognize them. Morse explains that children across the country are often familiar with identifying landmines due to years of regional fighting, but may not be as aware of the various unexploded ordnance, often remnants of American operations, which continue to cause injuries and fatalities. "In the eastern part of the country, kids find cluster munitions that were dropped by the US. They play with them and it leads to the injury and death of 10-year-old children... unexploded ordnance is now the source of these injuries," he said.

US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Vietnamese politician and diplomat Le Duc Tho at the signing the Paris Peace Accords in 1973, which ended US involvement in the war.

MPI/Getty Images

Disputed legacy

Kissinger is often criticized for distancing himself from the consequences of wartime actions and the impact of the Cambodian campaign which he played a role in planning. A journal entry by Nixon's chief of staff described Kissinger as being "really excited" about the start of the bombing campaign in 1969.

During a 2014 interview with NPR, Kissinger avoided taking responsibility for the bombings in Cambodia and Laos, instead comparing them to the drone attacks in the Middle East authorized by President Obama and arguing that the B-52 campaigns were less deadly for civilians.

"The decisions made would likely have been made by any of you listening, given the same set of problems. It was a difficult choice for us, as it would have been for you," he said.

Today, government-run agencies and other organizations in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia are still working to clear explosive remnants of war. Experts have noted that the US government is now the largest funder of unexploded ordinance and landmine clearance in the world.

However, aid organizations involved in the matter emphasize the importance of not overlooking the long-term impact of conflict in the region. "There is a specific concern that resources dedicated to addressing the lasting effects of past conflicts in Southeast Asia and other regions could be at risk if funding is redirected to address new conflict-driven emergencies," said a representative from the Mines Advisory Group, a UK-based organization that clears explosives in countries like Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, in an interview with CNN.

"The global community has a moral responsibility to all those in the world whose lives continue to be blighted by the impact of wars that ended before many of them were even born."