Fascinating Discovery: Unearthed Ancient Brains Offer Clues to Mental Health

Recent research reveals that ancient human brains are more commonly found in archaeological findings than previously believed. The mystery of their preservation through the ages prompts intriguing questions about their role in understanding mental illness and historical civilizations.

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter to stay informed about fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements, and more.

Alexandra Morton-Hayward, a former undertaker turned academic, developed an interest in brains and how they decompose during her previous job.

"I have spent many years working with the deceased. In my experience, the brain tends to liquefy rather quickly after death," she explained. "That's why it was quite surprising for me to read a scientific paper mentioning a 2,500-year-old brain."

Currently pursuing a doctorate in forensic anthropology at the University of Oxford, Morton-Hayward has found that although intact brains are not as common as preserved bones, they surprisingly do hold up well in the archaeological record.

The anthropologist has gathered a special collection of data on 4,405 brains found by archaeologists. These brains have been discovered in various locations such as northern European peat bogs, Andean mountaintops, shipwrecks, desert tombs, and Victorian poorhouses. The oldest brain found dates back 12,000 years.

The main focus of Morton-Hayward's research is to explore how these brains manage to stay intact over thousands of years, thanks to at least four preservation methods at work.

CNN

Related article

10,000 brains in a basement: The dark and mysterious origins of Denmark’s psychiatric brain collection

However, the database will also provide new opportunities for research, according to Martin Wirenfeldt Nielsen, a senior physician and pathologist at South Denmark University Hospital. He is responsible for the medical brain collection at the University of Southern Denmark.

"This database will allow scientists to examine brain tissue from ancient times and investigate if diseases that exist today were also present in civilizations from many years ago, which were completely different from our current society," Wirenfeldt Nielsen explained in an email.

Studying brain tissue from individuals who have not been influenced by modern society can provide insights into whether our current lifestyle plays a role in the development of certain brain diseases we see today.

Fragments of brain were discovered in a heavily waterlogged grave of a person buried in a Victorian workhouse cemetery in Bristol, England, around 200 years ago. No other soft tissue survived amongst the bones. Alexandra L. Morton-Hayward.

Morton-Hayward researched old scientific writings and talked to experts to gather information about ancient brains. Unfortunately, not all the actual brain specimens are still around for further examination.

The oldest brains ever found were two 12,000-year-old brains discovered at a site in Russia in the 1920s. Researchers found them alongside woolly mammoth teeth, but it remains a mystery what ultimately happened to these ancient brains.

Morton-Hayward is based in Oxford, England, and she works in a lab where they have a collection of 570 ancient brains. These brains are stored in fridges in jars and plastic containers with secure lids, similar to takeout containers. The most ancient brain in their collection is an 8,000-year-old brain from the Stone Age in Sweden, which was placed on a spike before being buried in a lakebed.

Jose Filippini

Related article

Ancient DNA offers new evidence in long-standing syphilis theory

Morton-Hayward and her colleagues discovered four different ways in which brains, typically discolored and shrunken, were preserved. These factors are often associated with the climate or environment in which they were found. The findings were published on March 19 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences.

In dry and hot conditions, the brains were dehydrated in a way that resembled the deliberate embalming of mummies. In acidic peat bogs, the body was essentially tanned like leather. In cold regions, the brain was frozen. In some cases, the fats in the brain turned into "grave wax" through a process called saponification.

In about 1,328 cases, brains have been found to survive without other soft tissues decaying. This raises questions about why the brain can remain preserved while the rest of the body decomposes. Surprisingly, many of the oldest brains are kept intact in this mysterious way, according to Morton-Hayward.

Morton-Hayward suggests the existence of a fifth unknown mechanism that could be responsible for this preservation. It is hypothesized that this mechanism may involve a type of molecular crosslinking, possibly triggered by the presence of metals like iron. This could cause proteins and lipids in the brain to bind together, allowing the brain to remain in a preserved state.

The researchers found preserved brains in skulls that were damaged from trauma or the fossilization process. They don't think the skull's protective shell is responsible for this preservation, according to the study.

Wirenfeldt Nielsen said that brain tissue is very fragile and vulnerable, especially tissue from the central nervous system. It is remarkable to discover brain tissue preserved for so many years.

Shown here is the 1,000-year-old brain of a person excavated from the c. 10th century churchyard of Sint-Maartenskerk, in Ypres, Belgium. The folds of the tissue, which are still soft and wet, are stained orange with iron oxides.

This is the brain of a person who lived 1,000 years ago, found in the churchyard of Sint-Maartenskerk in Ypres, Belgium. The tissue still looks soft and wet, with orange stains from iron oxides.

Alexandra L. Morton-Hayward

Secrets waiting to be spilled?

Ancient DNA and proteins could possibly be extracted from the brains, unveiling secrets about the individuals they once belonged to. According to Morton-Hayward, this material has the potential to reveal information that cannot be obtained from molecular data extracted from bones and teeth.

The brain, being the most metabolically active organ in the human body, accounts for 2% of our body weight but consumes 20% of our energy. It is constantly engaged in various activities due to its complexity, resulting in a unique biomolecular composition. This complexity allows for a wealth of information to be uncovered, making it a valuable source for research.

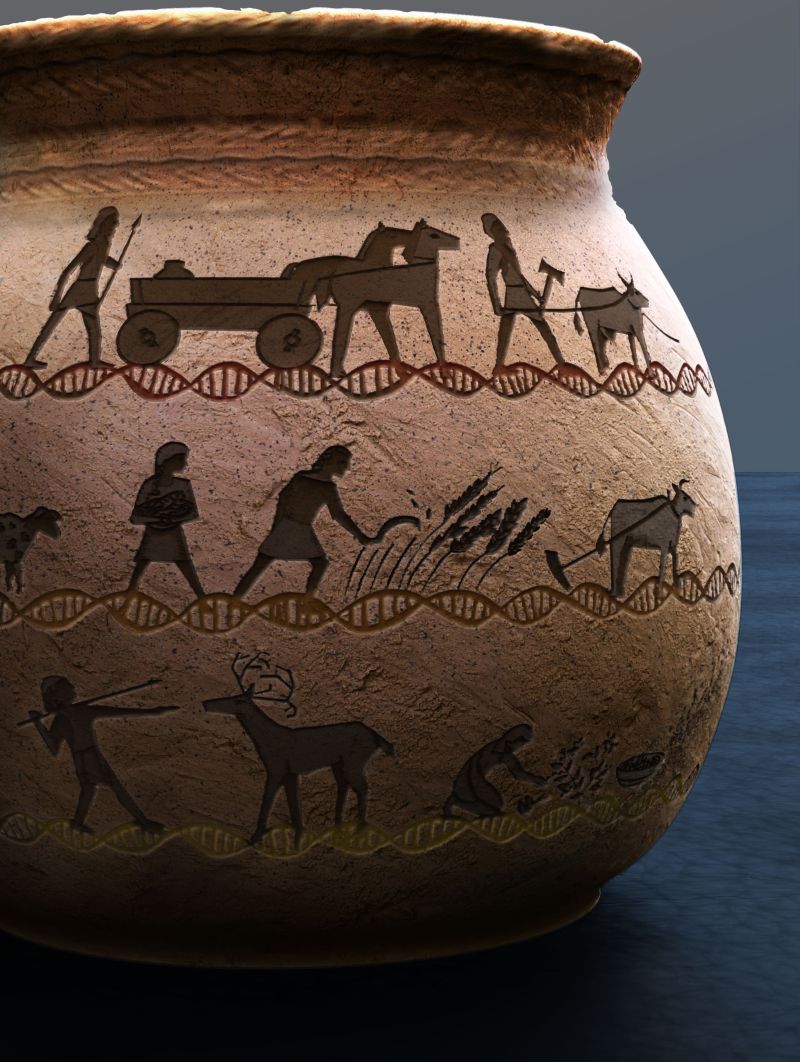

The researchers recovered DNA from the bones of ancient humans to better understand the genetic roots of disease.

The researchers recovered DNA from the bones of ancient humans to better understand the genetic roots of disease.

Sayo Studio

Related article

A gene that once protected humans 5,000 years ago may now be connected to a debilitating modern disease.

According to research, ancient DNA may be well-preserved within these brains due to their unique preservation process. The brains of the unknown type are condensing, shrinking, and driving out water, creating a closed system that could potentially protect high-quality DNA.

Many of the individuals who owned the brains have fascinating stories that deserve greater recognition, according to Morton-Hayward. One of the brains she studied belonged to a Polish saint, while another was from a victim of an Inca sacrifice. Having worked as an undertaker in the past, she emphasized the importance of remembering the people behind the body parts.

"I am thankful for the opportunity to have had that experience," she expressed. "It is crucial to always remember that these samples represent real human beings."

Editor's P/S:

The article delves into the intriguing world of ancient brains, revealing their remarkable preservation and the potential secrets they hold. The research of Alexandra Morton-Hayward sheds light on the unexpected durability of brains, challenging the assumption of their rapid decomposition. The discovery of brains dating back thousands of years, such as the 12,000-year-old specimens found in Russia, raises questions about the mechanisms that allow them to withstand the passage of time.

The study identifies four primary preservation methods, including dehydration, acid tanning, freezing, and saponification. However, the existence of isolated brain preservation without the decay of other soft tissues remains a mystery, hinting at the possibility of additional unknown mechanisms. The potential for extracting ancient DNA and proteins from these brains offers exciting opportunities to unlock secrets about the individuals they belonged to, providing insights into their health, diet, and genetic makeup. The article highlights the importance of recognizing the human stories behind these ancient specimens, fostering a deeper understanding of our shared past and the fragility of life.