Ancient Facial Piercings Unearthed in Turkey, Marking Archaeological Milestone

Discoveries of ancient facial piercings dating back 12,000 years have reshaped our understanding of personal adornment history. In a groundbreaking find, these artifacts are now linked directly to wearers' skulls, unveiling a new perspective on ancient body modification practices.

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter to stay updated on the latest news about fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements, and more.

Discoveries in Turkey by archaeologists have revealed groundbreaking evidence linking prehistoric facial piercings to the individuals who once adorned them.

Personal adornment, including objects resembling earrings for piercings, has been found among Neolithic peoples in southwest Asia dating back 12,000 years ago. However, there has been no direct association between these objects and the body parts they were worn on.

Recent excavations at Boncuklu Tarla in southeastern Turkey have uncovered burials where adornments for piercings were placed near the ears and mouths of the deceased. The remains, dating to around 11,000 years ago, showed dental wear on the lower incisors similar to patterns caused by wearing a labret, a type of ornament usually worn below the lower lip.

stone tool possibly from Layer VII at Korolevo I. Surface find.

stone tool possibly from Layer VII at Korolevo I. Surface find.

Roman Garba

Related article

Researchers reported in the journal Antiquity that facial piercings in Neolithic people from southwestern Asia have been directly linked to the body parts they perforated. This is the first time such a connection has been made, confirming that the practice was common during the early Neolithic period.

At Boncuklu Tarla, people of all ages were laid to rest, but the newly discovered ornaments were only found near the adults. This indicates that these decorations were likely not worn by children. Instead, it is believed that obtaining these piercings may have been a significant part of coming-of-age ceremonies within the community, as suggested by the study findings.

According to anthropological archaeologist Dusan Boric, an associate professor at Sapienza Università di Roma in Italy, there are various forms of evidence that point towards coming-of-age rituals during the Neolithic period. This includes burials where the body is positioned with specific artifacts, or where the deceased is placed in designated locations meant for a particular age group.

“But I cannot thinkof many other examples as convincing as this one,” said Boric, who wasnot involved in the study.

Shown here is one of the skulls from Boncuklu Tarla as it was found in the grave, with artifacts nearby. The object labeled "a" is an ear piercing, and the one labeled "b" is a lip piercing called a labret.

One of the skulls from Boncuklu Tarla is displayed here as it was discovered in the grave, surrounded by artifacts. The item marked as "a" is an ear piercing, while the one labeled "b" is a lip piercing known as a labret.

Emma L. Baysal

Incredible Amount of Artifacts

Hunter-gatherers lived in Boncuklu Tarla from about 10,300 BC to 7100 BC when people started to settle down. The site was initially dug up in 2012 and has uncovered a large number of decorative objects from the Neolithic era. Around 100,000 ornamental artifacts have been discovered so far, which amazed study coauthor Dr. Emma L. Baysal, who is an associate professor of archaeology at Ankara University in Turkey.

"The amount of beads found at this site is truly astonishing. According to Baysal, this is a place where people absolutely love decoration more than anywhere else. They had a huge collection of beads and created intricate items such as necklaces, bracelets, animal-shaped pendants, and decorative pieces that could be sewn onto clothing."

Hala Alarashi, Alice Burkhardt and Ba`ja N.P.

Related article

An ornate necklace was discovered in the grave site of a child and carefully put back together.

In addition to the necklace, they also made jewelry for the ears and lips. Labrets, which are still worn in certain cultures in Amazonia and Africa, can be found in different shapes such as rounded, oblong, and disc-shaped. Some are long and thin, while most have one end that is wider and flattened. They vary in diameter and width.

Scientists have found 85 ornaments in Boncuklu Tarla burials that were worn as piercings. These ornaments were made from materials like flint, limestone, copper, and obsidian. The labrets were classified into seven types based on their shape. They all measured at least 0.3 inches (7 millimeters) in diameter, with the longest one being just over 2 inches (50 millimeters) in length.

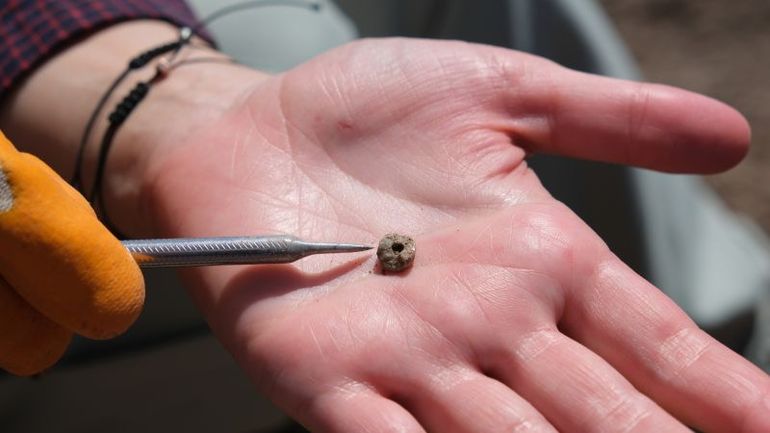

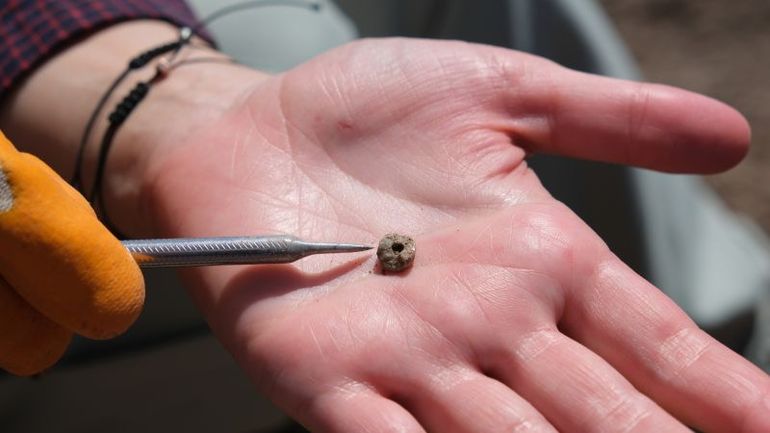

Archaeologists at Boncuklu Tarla in southeastern Turkey unearthed artifacts that were used as body piercings.

Archaeologists at Boncuklu Tarla in southeastern Turkey unearthed artifacts that were used as body piercings.

Emma L. Baysal

Ornaments known as Type 1 were described as having long shafts and a "nail-like appearance" and were likely worn by being inserted into the flesh or cartilage of the ear. Types 2, 4, and 6, which were elongated, were also believed to be ear ornaments. In contrast, Types 3 and 5 labrets had shorter, more rounded shafts, making them more suitable for lip wear. Type 7, a flattened disc, was considered a type of labret.

Some of the labrets had been moved from their original positions in the graves, possibly by rodents, but they were still found near the head and neck area of the human remains. Other pieces were still in place on the upper or lower surface of the skull or under the lower jaw, as mentioned by the study authors.

Scientists have believed for a long time that Neolithic labrets were used as piercings, particularly around the mouth or ear, according to Dusan. However, new and strong contextual evidence from the site of Boncuklu Tarla suggests that these objects were actually linked to these body parts. They were discovered in burials and were probably worn in the same manner during life.

Researchers concluded that facial piercings, such as ear ornaments or labrets, were reserved for adults based on the absence of these adornments near the heads, necks, or chests of buried children who were found with pendants and beads.

Baysal suggested that the desire for body decoration may be linked to ideas of maturity or social status.

According to Baysal, piercings and other forms of body adornment are crucial for archaeologists studying how ancient societies communicated with each other and outsiders. These decorations provide valuable insights into the people of that time, especially before the invention of writing.

Here are seven different types of labrets discovered at Boncuklu Tarla that were used as body piercings: Type 1: c1–3; Type 2: a1 and a4; Type 3: a2 and a3; Type 4: c4; Type 5: b1 and b2; Type 6: d1–6; Type 7: e.

Shown here are examples of seven types of labrets found at Boncuklu Tarla that were used as body piercings: Type 1: c1–3; Type 2: a1 and a4; Type 3: a2 and a3; Type 4: c4; Type 5: b1 and b2; Type 6: d1–6; Type 7: e.

Emma L. Baysal

Dusan mentioned that the way people express themselves through personal adornment may have origins in the mythologies of traditional societies. In these societies, there are myths that explain the significance of ornaments and body decoration. These myths suggest that decorating the body is not just about looking good, but it could also be about creating one's identity and protecting oneself.

Adornments like earrings and other personal ornaments provide a glimpse into the lives of Neolithic people. These items not only served as tools or artifacts of daily life but also reflected a universal human desire to express identity and community through piercings.

According to Baysal, wearing earrings is not just for oneself, but also for how one is perceived by others. This practice of adorning oneself to project a certain image has remained consistent throughout history. It allows us to connect with people from the past and realize that they were not so different from us.

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American and How It Works magazine.

Editor's P/S:

The discovery of prehistoric facial piercings in Turkey offers tantalizing insights into the lives and rituals of our ancestors. The direct association between the adornments and body parts, such as ears and lips, provides tangible evidence of these practices during the Neolithic period. The absence of such adornments near children suggests that facial piercings may have been a significant part of coming-of-age ceremonies, marking the transition into adulthood.

This discovery underscores the importance of body adornment in human cultures throughout history. Piercings, beads, and other ornaments have served not only as decorative elements but also as symbols of identity, status, and connection to community. The universal desire to express oneself through personal adornment transcends time, linking us to our Neolithic predecessors and highlighting the enduring human need for self-expression and connection.