Unveiling Untold Stories: Japanese American Prisoner Art Unveils Struggles of WWII Detention Camps

Imprisoned Japanese American artists showcased their powerful artwork at the residence of US Ambassador to Japan, Rahm Emanuel Their thought-provoking pieces vividly portray life in WWII detention camps, shedding light on a regrettable chapter in American history

In an ink drawing, two siblings tightly hold onto their belongings - a few bags and suitcases marked with the inscription "13660." The same number is attached to their clothing, symbolizing the identification given to their family upon entering the detention camp.

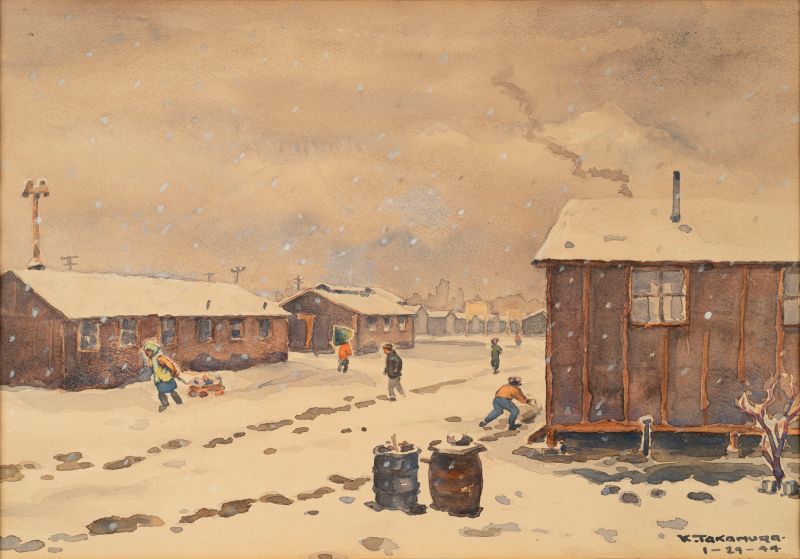

In another artwork, a watercolor depiction captures rows of barracks resembling army-style structures amidst the winter season. Detainees can be seen making their way through the snow, trudging between the buildings.

These are only a couple among nearly 20 artworks created by Japanese American artists who were unjustly incarcerated in the United States during World War II. Recently showcased in Tokyo, the exhibition not only shed light on the harrowing experiences of these prisoners but also carried significant symbolism as it took place at the official residence of US Ambassador to Japan, Rahm Emanuel.

This event represents an increasing demand for a more comprehensive acknowledgement of a controversial chapter in American history.

A tranquil watercolor by imprisoned artist Kango Takamura depicts a winter's day at the Manzanar camp in California's Owens Valley.

Courtesy Japanese American National Museum

The internment of Japanese Americans, a majority of whom were American citizens, was ordered by Franklin Roosevelt through an executive order after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. This event marked the largest forced relocation in the history of the United States, resulting in approximately 120,000 individuals of Japanese heritage being imprisoned throughout the country.

Although the US government issued a formal apology in 1988 and offered $20,000 in reparations to surviving detainees, the lasting impact of this period continues to shape the lives of Japanese and Asian Americans for generations.

The battle of a family to reunite with artwork looted by the Nazis is a significant story. Robert T. Fujioka, the vice chair of the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in California, places great importance on highlighting this history, particularly with the ongoing surge of racism and xenophobia targeted towards individuals of Asian descent due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

He expressed to CNN during the exhibition reception that this current racist situation is the worst it has been since World War II. He emphasized the importance of continuously telling this story, urging people to conduct their research and educate themselves about it. Otherwise, he believed that society would be at a standstill. Additionally, he stressed the need to consistently remind people about the essence of democracy.

An illustration from Miné Okubos graphic memoir, "Citizen 13660," depicts the artist and her brother with the only belongings they were allowed to take into the camp.

The artworks, currently exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in Wakayama, Japan, also serve as a poignant preservation of vanishing first-hand memories from the camps. It is worth noting that all the artists whose works were showcased have since passed away.

"It is truly gratifying to see this exhibit being presented in Japan by a prominent US official. This not only showcases a commitment to preserving and disseminating this significant history beyond the borders of the US but also highlights the profound impact of artists in capturing and preserving the visual narrative of the camp experience, especially considering the prohibition on cameras," stated Alice Yang, the chair of the history department at the University of California Santa Cruz. Yang has extensively delved into the study of Japanese American detention and the subsequent quest for reparations, although she was not directly engaged in the exhibition.

Depicting incarceration

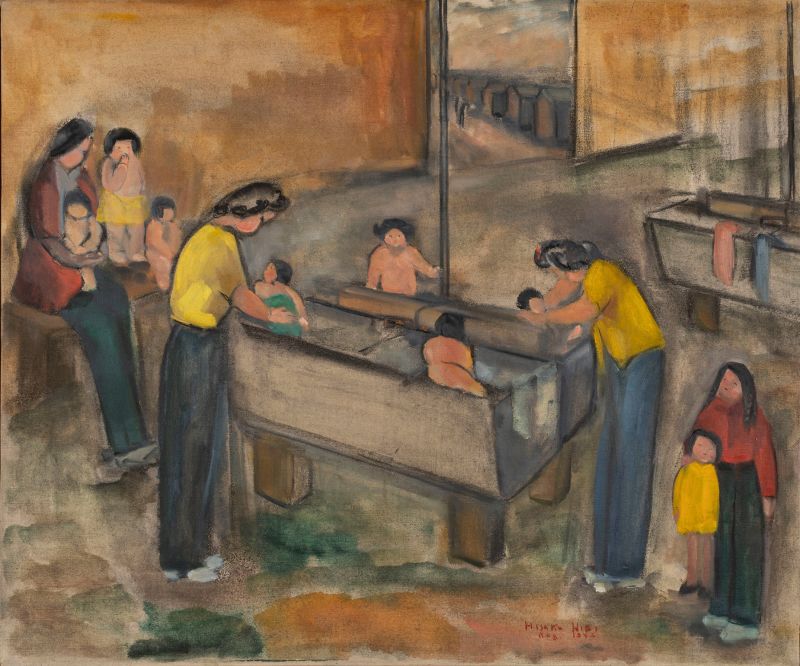

The artwork covers a wide variety of mediums, including oil paintings and pen drawings. The themes explored are equally varied. Showcasing everyday scenes, such as women washing clothes in open troughs or men passing the time playing cards, many of these pieces capture people carrying on with their lives as usual.

The content provides insight into the emotional struggles of incarcerated individuals, including a collection of portraits by influential artist Hisako Hibi. Having experienced imprisonment in California and Utah after immigrating to the US as a child, Hibi captured her children's lives at the camps in her artwork. One notable piece, titled "Study," depicts her children seated at desks, engrossed in writing. Yang, an authority on Hibi's work, commends her ability to produce over 70 paintings and countless sketches while raising two children in Topaz, a large camp housing numerous prisoners in Utah.

Hisako Hibi's "Laundry Room" depicts everyday life in a Utah prison camp that held thousands of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Courtesy Japanese American National Museum

Yang added that the collections diversity reflects the varied experiences of detaineesperspectives that were overlooked by US officials at the time.

Hibi and her fellow artist Miné Okubo depicted the lives of female prisoners, highlighting their lack of privacy in shared bathrooms. This stark contrasted with the government's portrayal of women as golden-star mothers and camp employees, according to Yang. In Edo Japan, this exceptional female painter was highly sought after for her exquisite ink paintings.

Detainees exhibited varying attitudes towards the war and President Roosevelt's executive order. According to Fujioka, his grandfather expressed that "the United States is the greatest country in the world" as he was sent to Jerome War Relocation Center in Arkansas, despite tears streaming down his face. Fujioka, a vice chair at JANM, emotionally recounted that many inmates, including his mother, hoped that their cooperation would serve as proof of their Americanness to their captors.

On the other hand, some individuals resisted the executive order, with Fred Korematsu being the most notable example. Korematsu initially went into hiding to avoid incarceration but was eventually captured and imprisoned. He later filed a lawsuit against the US government, which was ruled against by the Supreme Court in 1944. However, this infamous decision was eventually overturned by the same court in 2018.

Robert T. Fujioka, Vice Chairman of the Japanese American National Museum, stood alongside "Fresh Air Break from Fresno to Jerome Camp," a painting by Henry Sugimoto. The artwork portrays the camp where Fujioka's mother and grandfather were confined.

During this challenging period, imprisoned artists diligently recorded their experiences, utilizing whatever resources they could access. Remarkably, Henry Sugimoto employed unconventional canvases such as pillowcases, bedsheets, and canvas mattress covers to showcase his artistic talent.

Preserving a legacy

"I believe that everyone recognized the importance of capturing the moment, in order to document the gravity of the entire situation," stated Fujioka. "They were conscious that there would be a future time where this would hold significance, as they were essentially recording history."The exhibition's location at the US ambassador's residence was highly symbolic, mirroring the historical significance of the venue. The artworks were displayed in the very room where General Douglas MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito held their historic meeting following Japan's surrender in 1945. Ambassador Rahm Emanuel, in explaining the choice, highlighted the rich history encompassed within the drawing room and the entire building.

The incarceration of Japanese Americans, according to Emanuel, constituted a "shameful" episode in the annals of American history. "However, an integral part of the American narrative is acknowledging that shame, assuming responsibility for it. Embracing democracy and being part of America entails drawing lessons from our past," he further emphasized.

"This heartfelt depiction of a domestic setting carries an intriguing twist—it was actually captured within the confines of an American detention camp," states a note displayed alongside Tokio Ueyama's masterpiece, "The Evacuee."

Kindly provided by the Japanese American National Museum.

JANM President and CEO Ann Burroughs expressed to CNN during the exhibition that this event provides a chance to educate Japanese individuals about the profound and haunting chapter in both American and Japanese history.

Furthermore, the artworks aim to shed light on the hardships endured by those who were released from the camps once they were shut down. This incarcerated generation had suffered the loss of their homes and businesses, which left them with little to reclaim upon their release.

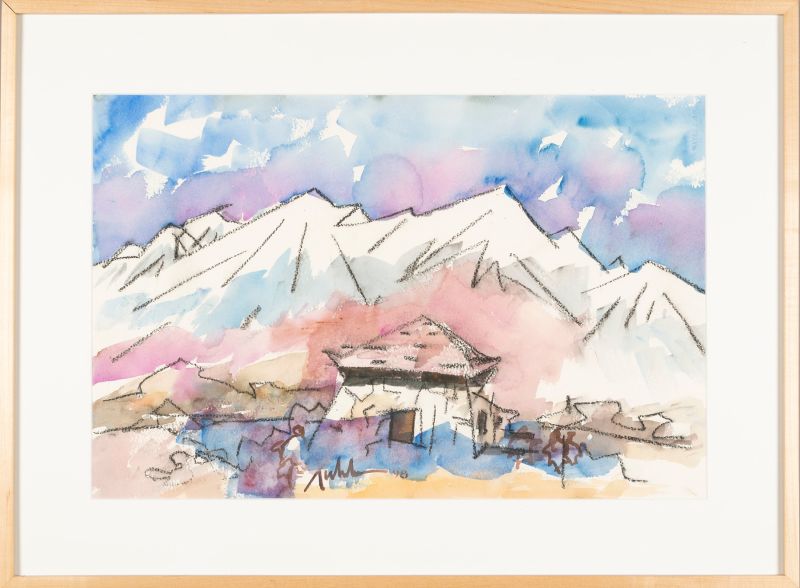

Vintage photographs offer a glimpse into the hidden aspects of Japan during its prosperous boom-era. Despite being renowned for his expressive oil paintings, Sugimoto faced extreme financial hardship after leaving the internment camp. Tragically, numerous pre-detention artworks of his, kept in storage, were auctioned off during the war, resulting in no financial gain for him. Similarly, Henry Fukuhara, another detainee, temporarily halted his artistic pursuits upon release in order to support his family and establish a business. It was only in the 1970s that he was able to resume his passion for drawing, painting, and printmaking.

An untitled watercolor produced by artist Henry Fukuhara on the former site of the California camp in which he was incarcerated with his family during World War II.

Courtesy of the Japanese American National Museum.

While facing weighty responsibilities, individuals like Hibi, for instance, managed to juggle their art along with raising two children on their own after their spouse's passing. Hibi accomplished this feat by working in a garment factory, all while pursuing painting and attending art classes. On the other hand, some individuals decided to devote themselves to activism and community service, specifically advocating for reparations.

The exhibited artists and their art "tell you that you can never squash and turn off the human spirit, and theres an act of resilience," Ambassador Emanuel said. "Theres a lesson from that, too."