Unveiling the Untouched Treasure Chest of French Correspondence: A 265-Year Revelation

Unlocking a 265-year-old treasure chest of lost French letters reveals captivating insights into untold stories and provides a fresh perspective on historical literacy

Discover the wonders of the universe through CNNs Wonder Theory science newsletter. Delve into captivating discoveries, groundbreaking scientific advancements, and beyond.

For over two and a half centuries, a collection of over 100 letters penned by family members to the men aboard the French warship Galatée remained untouched, entombed in stacks, and sealed with crimson wax as they never reached their intended addressees.

The ship was captured by the British in 1758 during the Seven Years War while it was sailing from Bordeaux to Quebec. As a result, the crew was imprisoned and the letters, which had almost reached the ship, were seized and given to the Admiralty of the British Royal Navy in London.

Recently, the letters have been opened and read for the very first time. Their contents provide a fascinating and rare historical context about various segments of society during that period, according to Renaud Morieux, the lead author of the study. Morieux is a professor of European history and a fellow at Pembroke College in Cambridge, United Kingdom. The study was published in the French journal Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales on Monday.

Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San Jose State University

"These letters provide insights into universal human experiences that transcend time and borders," stated Morieux. "They shed light on how we confront significant life obstacles. Whether it's being separated from loved ones due to uncontrollable events like pandemics or wars, we must find ways to maintain communication, offer reassurance, and keep our passion alive. Today, we have tools like Zoom and WhatsApp. However, in the 18th century, people solely relied on letters, yet the emotions they conveyed feel remarkably familiar."

A significant portion of the correspondences comprises love letters from wives to their sailor husbands, expressing their longing for reunion or anxiously awaiting news about their loved ones' safety.

Approximately 59% of these letters were signed by women, providing valuable insights into literacy levels across different social classes and shedding light on the experiences of those who held important responsibilities at home while their husbands embarked on seafaring journeys.

"I am your forever faithful wife, Marie Dubosc, and I could dedicate the entire night to penning my thoughts to you," she wrote. "As midnight approaches, I believe it is appropriate for me to retire for some much-needed rest, my dear friend." Sadly, this heartfelt letter never reached Louis Chambrelan, her husband and the first lieutenant of the ship. Tragically, Dubosc passed away in 1759, possibly before her release following captivity. Chambrelan returned to France and remarried in 1761, never having the chance to see his beloved wife again.

"These letters challenge the outdated belief that war is solely a male endeavor," Morieux noted in an email to CNN. "During the absence of their male counterparts, women assumed responsibility for managing the household's economy and made pivotal economic and political choices."

Reflecting on the written expressions from bygone eras.

While conducting research for his book "The Society of Prisoners: Anglo-French War and Incarceration in the Eighteenth Century," Morieux stumbled upon a box of letters at the National Archives in the UK. The bundle of letters was neatly tied with a ribbon. Curious about their contents, Morieux sought permission to open the sealed letters and was delighted when his request was granted. Upon unsealing the letters, he described the experience as discovering a hidden treasure chest.

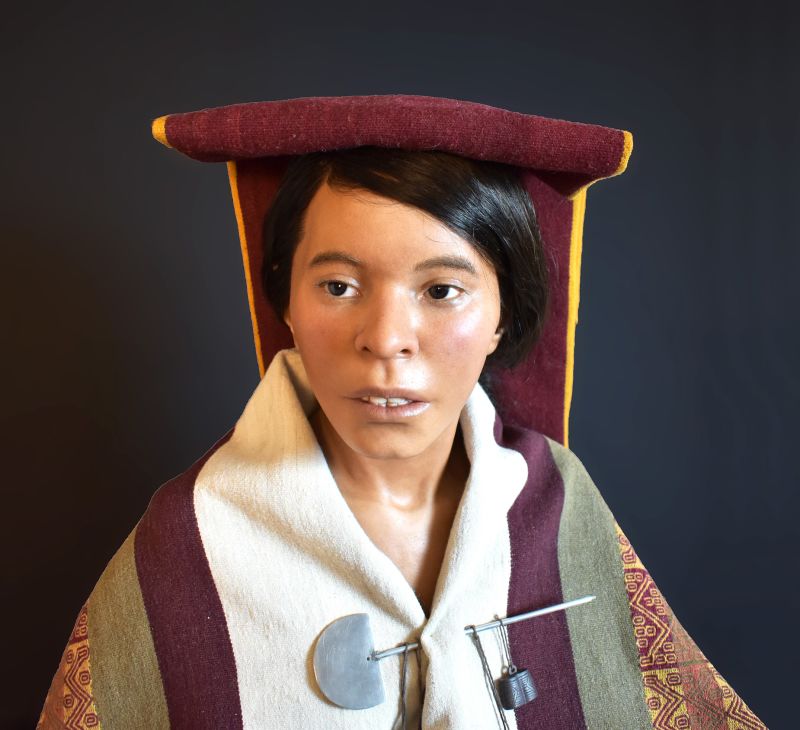

Dagmara Socha

Morieux described the experience of being the first person to read letters not intended for her as a one-of-a-kind moment. She mentioned how the letters seemed to be eagerly awaiting her to open them.

The French postal administration initially attempted to deliver the letters to the ship by sending them to various ports, unaware that the ship had been captured and sold. Despite possessing impressive ships, the French lacked experienced sailors, prompting the British to seize as many of them as possible, according to Morieux. Throughout the Seven Years War, British forces managed to capture and imprison a total of 64,373 French sailors.

While some prisoners of war succumbed to malnutrition or disease, many were eventually released. Nevertheless, the families of these sailors faced a distressing and challenging task in attempting to contact their loved ones and ascertain their well-being. Prior to their capture, the Galatée was stationed in Brest, France, which was afflicted by a devastating typhus outbreak.

In order to connect with their loved ones, family members may face difficulties and resort to sending several copies of a letter to various ports or ask fellow crew members' families to mention them in their own letters.

"These letters illustrate the strength of societies during difficult and challenging times," remarked Morieux. "Furthermore, they showcase people's resourcefulness in overcoming the obstacles of distance and absence. They had to depend on their families, friends, and neighbors to facilitate the exchange of information."

According to Morieux, British officials examined and perused the contents of two letters in order to determine if they held any valuable information. However, upon discovering that the letters merely contained "family stuff," they were subsequently stored away.

Morieux immersed himself in the letters, filled with numerous misspellings, cramped handwriting that filled every corner of the paper, and a shortage of punctuation. Additionally, he painstakingly identified each member of the 181-person crew, discovering that the letters were primarily intended for approximately a quarter of them.

One particular story that caught Morieux's attention unfolded through multiple letters: he came across heartfelt messages from a concerned mother longing for direct communication from her son, as well as correspondence from his fiancée, who found herself entangled in a timeless family dilemma.

Using a scribe, the mother sent letters to her son, young sailor Nicolas Quesnel, expressing her dissatisfaction that he wrote more to his fiancée than to her.

"On January 1st, you chose to write to your fiancée instead (…). It seems that I think more about you than you do about me. (…) Nevertheless, I wish you a happy new year filled with blessings from the Lord. I believe my health is deteriorating, as I have been unwell for three weeks. Please pass on my regards to Varin (a fellow sailor), as it appears that only his wife shares news of you with me," mentioned Marguerite, the 61-year-old mother, in her letter.

Marguerite, the 61-year-old mother of a young sailor named Nicolas Quesnel, dictated a letter to him saying she was "for the tomb."

Marianne, the fiancée of Quesnel, wrote a separate letter to defend her future mother-in-law, Marguerite, in order to prevent any discomfort as Marguerite appeared to hold Marianne responsible for the lack of communication from her son.

"The dark cloud has vanished, as your mother received a letter from you that brightened the atmosphere," Marianne penned.

However, Marguerite came back with additional grievances. "You never acknowledge your father in your letters, and this greatly distresses me. Please remember to include your father in your next correspondence," his mother's letter conveyed. Marguerite was referring to his stepfather, whom she had married following the passing of Quesnel's biological father.

"Here is a son who clearly despises or denies the man as being his father," stated Morieux. "However, in such circumstances, when your mother remarries, her new spouse automatically assumes the role of your father. Without explicitly stating it, Marguerite is subtly urging her son to show respect by informing him about his father. These intricate yet commonplace family tensions reveal new perspectives on literacy."

Several letters contained information indicating that they were written by scriveners, individuals who would write and read on behalf of others. These scriveners would occasionally include a message like "the scrivener sends their regards" within the letter.

"It wasn't necessary to possess the ability to read or write in order to participate in the epistolary culture," stated Morieux. "These letters provide insight into a peculiar era when the boundaries between private and public were not as distinct as they are today: one could discuss matters of love and even express physical desires for their spouse...all within a letter dictated to someone else or intended for others to read."

One example was a letter from Anne Le Cerf to her husband, an officer on the ship. "I cannot wait to possess you," she wrote, which could mean "embrace" or "make love."

Anne Le Cerf, who signed her letter with a nickname "Nanette," wrote a love letter to husband, Jean Topsent.

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Morieux's interest lies in discovering additional information about the crew and their fate, including any surviving letters they may have written during their time in captivity. The captivating contents of the letters exchanged amongst the crew members of the Galatée have intrigued him, motivating him to continue unraveling their stories.

"Finding first-person accounts from individuals belonging to a specific social class, particularly before the twentieth century when literacy rates were lower, is quite uncommon for historians," Morieux expressed. "Gaining access to the writings of women, particularly the wives of sailors, is truly exceptional. This provides us with invaluable insights into their emotions, encompassing fear, anxiety, anger, jealousy, as well as their unwavering faith or the significant role they played in managing the household while their husband, son, or brother was absent."