Unveiling the Untold Story of a 19th Century Portrait Painter

Explore the latest revelation surrounding the renowned portraitist John Singer Sargent as he emerges in a fresh and intriguing perspective, shedding new light on his artistic legacy.

In the spring of 1888, New York socialite Eleanora Iselin eagerly welcomed portrait artist John Singer Sargent into her home. She was excited about having her expensive and refined taste captured on canvas. Iselin even had her maid bring in her best Parisian frocks for the occasion.

However, to Iselin's dismay, the renowned painter wanted to capture her in what she was wearing at that moment, not in her fancy clothes. The result was a slightly stern and removed portrait of Iselin in a black satin day dress against a muddy-brown backdrop. This portrait is now one of the main attractions in the "Sargent and Fashion" exhibition at the Tate Britain until July 7.

However, the French finery she anticipated was missing. Instead, Iselin's dress had a mesmerizing satin finish, with glinting embellishments on her corset and protruding ruffles on her white lace sleeves.

Despite curating a selection of her best frocks, Eleanor Iselin was captured in her casual day dress at the insistence of Sargent.

Despite curating a selection of her best frocks, Eleanor Iselin was captured in her casual day dress at the insistence of Sargent.

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington/Tate Britain

"He doesn't just flatter you," curator James Finch told CNN Style at the London gallery. "It's not a servitudinal relationship. It's a creative one in which each portrait emerges in its own unpredictable way."

'Will it paint?'

There have been numerous reviews of the 19th century painter's work, focusing on his distinctive high-society portraits and watercolor landscapes. However, "Sargent in Fashion," a collaboration with Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, presents the artist in a fresh light.

During the era of haute couture's rise, Sargent and his subjects were immersed in a new era of fashion. According to Finch, the prominence of couturiers increased during this time. Many aspects that are now considered standard in the fashion industry, such as seasonal collections, runways, and clothes modeled by actual people rather than mannequins, were all being introduced for the first time.

Women with Dove (formerly called Marie Laurencin and Nicole Groult). 1919. Oil on canvas. 61.5 x 50 cm. LUX.0.104P. Photo: Jacques Faujour

Women with Dove (formerly called Marie Laurencin and Nicole Groult). 1919. Oil on canvas. 61.5 x 50 cm. LUX.0.104P. Photo: Jacques Faujour

Jacques Faujour/Fondation Foujita/Artists Rights Society, New York/ADAGP, Paris/Courtesy Barnes Foundation

The 1920s painter who hid sapphic symbols in her portraits

This new, exciting era in fashion not only captivated artist John Singer Sargeant but also influenced the desires of his clients. Scottish critic Margaret Oliphant observed in 1878 that there was a growing class of people who dressed based on paintings, asking whether their garments would look good in a portrait. Fashion was no longer just about showing off wealth and status; it became a means of self-expression, creativity, and artistry. Designers, recognized for their unique perspectives and skills, were no longer just dressmakers but revered artists with devoted followings. As Edith Wharton noted in 1920, fashion became a form of "armor," symbolizing strength and power.

The artist as stylist

While painting clothing is a skill all portrait artists must master, Sargent’s approach to his sitter’s outfits was unique. He had a strong desire to control every aspect of the image, including the clothing his subjects wore. In Sargent's view, the colors, textures, fabric finishes, and silhouettes played a crucial role in creating harmony in the portrait and could not be left to chance.

Sargent often disregarded the clothing preferences of his sitters, as seen in the case of poor Iselin. He carefully shaped what was worn or at least what was visible. For instance, in 1903, Sargent painted mother and daughter, Gretchen and Rachel Warren, at Fenway Court in Boston (now known as the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum). The pair is depicted sitting closely, almost intertwined, with Rachel’s head resting on her mother’s shoulder. The pink hue of Rachel’s dress intensifies their flushed cheeks. However, it was not a dress at all. According to the exhibition, the young girl had arrived wearing an ill-fitting dress of the wrong shade. Instead of settling for it, Sargent draped a yard of rose-colored fabric around her. As the portrait neared completion, the piece of cloth had transformed on the canvas into a flowing, diaphanous dress.

Gretchen and her daughter Rachel Warren were captured by Sargent in 1903, standing side by side. Rachel was dressed in a piece of pink fabric that Sargent skillfully transformed into a dress on canvas.

Finch, from CNN, mentioned that the artist is not simply capturing what he sees in front of him. Instead, he is actively involved in the painting, much like a stylist or a fashion director.

Sargent often asked top couture houses to design dresses for his portrait subjects. In 1922, he had English designer Charles Fredrick Worth create a special black velvet gown and cape for his close friend Sybil Sassoon. Worth, known for founding the House of Worth, added metal thread lace trim and a striking mauve collar to the outfit. Sargent cleverly incorporated the purple hues of the dress into Sassoon's complexion and a small flower in her hand.

This approach offers a fresh perspective on Sargent's portraits, providing a new way to appreciate his attention to detail and ability to capture the essence of his subjects.

Reframing a centuries-old master as something new to be discovered is quite a challenge. Renowned paintings like “Carnation, Lily, Lily Rose” (1885-86), usually seen in a dark, red corner of the gallery, are now recontextualized against a soft periwinkle display wall. This design enhances the painting’s evening light.

In collaboration with the Boston Museum of Fine Arts textile department, many works on display are paired with their original gown. Sybil Sassoon’s brooding black taffeta opera cloak may seem flat compared to its five-foot illustrative counterpart, but the dressed mannequins provide a three-dimensional glimpse into Sargent’s world.

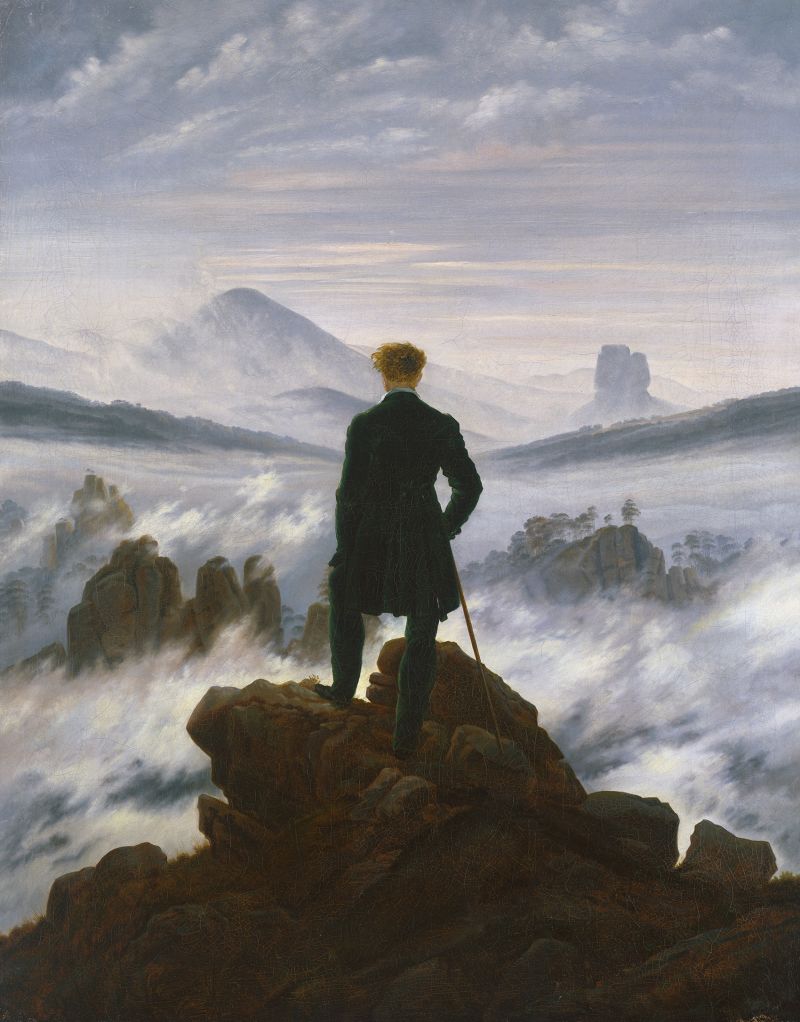

Caspar David Friedrich (1774â1840) Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, c. 1817 Oil on canvas, 94.8 x 74.8 cm Permanent loan from the Stiftung Hamburger Kunstsammlungen

Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840)Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, c. 1817Oil on canvas, 94.8 x 74.8 cmPermanent loan from the Stiftung Hamburger Kunstsammlungen

SHK/Hamburger Kunsthalle/bpk

Revered by Hitler, this painter fell out of favor. Now the art world is taking notice again

"It offers a fresh perspective on the portraits," Finch explained. "When you look at these clothing items, you start to ponder about the individuals who once wore them, the journey of these dresses through time, and how they have been cherished and handed down from one generation to the next. It's fascinating to think about how these garments were often altered to fit different body shapes over the years. I believe many people can relate to these stories."

The show pairs portraits with the original costume worn by the sitter, as demonstrated here with Sargent rendition of actor Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth in 1889.

The show pairs portraits with the original costume worn by the sitter, as demonstrated here with Sargent rendition of actor Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth in 1889.

Jai Monaghan/Tate Britain

Sargent's work was ready-to-wear, while Sargent's work was bespoke. However, not everyone was happy about the reevaluation of Sargent's work. One British art critic criticized the exhibition during opening week, describing it as "horrible" and filled with "old clothes." Despite this, Finch believes that presenting Sargent's work alongside garments does not diminish the value of previous research on him.

In fact, the exhibition shows how Sargent's skill in capturing inner worlds through facial expressions was actually enhanced by his interest in clothes. For example, by observing Iselin dealing with a fashion emergency, we learn more about her character than if Sargent had allowed her to wear anything she wanted.

"A lot of Sargent's peers focused on formalism," explained Finch. "Their portraits were like ready-to-wear clothing, using standard elements, while Sargent's work was always customized. Each portrait was unique."

Editor's P/S:

This article offers a captivating glimpse into the intricate world of John Singer Sargent, a renowned 19th-century portrait artist. Through his meticulous attention to detail and insistence on controlling his subjects' attire, Sargent created works that transcended mere representation. The exhibition's unique juxtaposition of portraits with their original garments provides a fresh perspective, revealing the artist as a pioneer in the intersection of art and fashion.

Sargent's unwavering pursuit of harmony in his compositions extended to the clothing his subjects wore. By carefully shaping and selecting each garment, he orchestrated a symphony of colors, textures, and silhouettes that enhanced the emotional resonance of his portraits. His refusal to conform to his sitters' fashion preferences, as exemplified in the case of Eleanora Iselin, demonstrates his commitment to artistic integrity. Through his unwavering vision, Sargent captured not only the outward appearance of his subjects but also the complexities of their inner worlds.