Unveiling the Untold Stories: Intricate Artwork Unveils Life in WWII Japanese American Detention Camps

Imprisoned Japanese American artists showcased their powerful artwork at the US Ambassador's residence in Japan The collection sheds light on the dark chapter of WWII detention camps, leaving an indelible legacy for future generations

In a captivating ink illustration, two siblings tightly hold onto their meager belongings - a small collection of bags and suitcases - all marked with the distinct label "13660." These exact digits are also prominently attached to their clothing, symbolizing the assigned number of their family as they prepare to enter the detention camp.

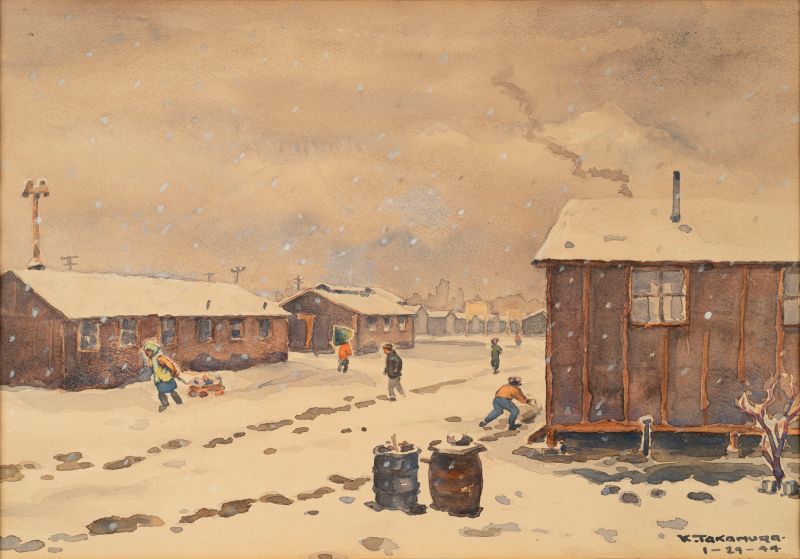

In another poignant portrayal captured through watercolor, rows of barracks reminiscent of army structures stand amidst the harsh grip of winter. Within this desolate scene, detainees can be seen trudging wearily through the snow, moving between the barracks with solemn determination.

These are merely a couple of nearly 20 pieces created by Japanese American artists who were imprisoned in the United States throughout World War II and showcased in Tokyo recently. In addition to shedding light on the often overlooked experiences of these prisoners, the exhibition, held at the official residence of US Ambassador to Japan, Rahm Emanuel, served as a symbolic gesture towards the increasing demand for a more comprehensive acknowledgment of a controversial chapter in American history.

A tranquil watercolor by imprisoned artist Kango Takamura depicts a winter's day at the Manzanar camp in California's Owens Valley.

Courtesy Japanese American National Museum

Following the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941, Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order that led to the detention of Japanese Americans, the majority of whom were US citizens. This action, which involved approximately 120,000 individuals of Japanese descent, constituted the largest forced relocation in the history of the United States. Although the US government apologized in 1988 and provided reparations of $20,000 to each surviving detainee, the lasting impact of this traumatic experience reverberated through generations of Japanese and Asian Americans.

One family's fight to reclaim art stolen by the Nazis comes to light.

Highlighting this historical event holds great significance for Robert T. Fujioka, Vice Chair of California's Japanese American National Museum (JANM). As the increased racism and xenophobia towards individuals of Asian background persists in the aftermath of Covid-19, the importance of shedding light on this story has become even more crucial.

He expressed to CNN at the exhibition reception that this racist situation has reached an unprecedented level since World War II. He emphasized the importance of consistently sharing and educating others about this story. Failing to do so would be equivalent to surrendering. It is crucial to consistently reinforce the understanding of democracy among individuals.

An illustration from Miné Okubos graphic memoir, "Citizen 13660," depicts the artist and her brother with the only belongings they were allowed to take into the camp.

The artworks, currently exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in Wakayama, Japan, serve as a means to safeguard vanishing firsthand memories of the camps. The artists behind these works have all since passed away.

Alice Yang, chair of the history department at the University of California Santa Cruz and an expert in Japanese American detention, expressed her gratification at the exhibit being shown in Japan by a prominent US official. According to Yang, this demonstrates a dedication to remembering and sharing this history beyond the borders of the US. She also noted the significance of artists in capturing a visual record of the camp experience, as cameras were prohibited. Although not directly involved in the exhibition, Yang emphasized the importance of drawing attention to this aspect.

Depicting incarceration

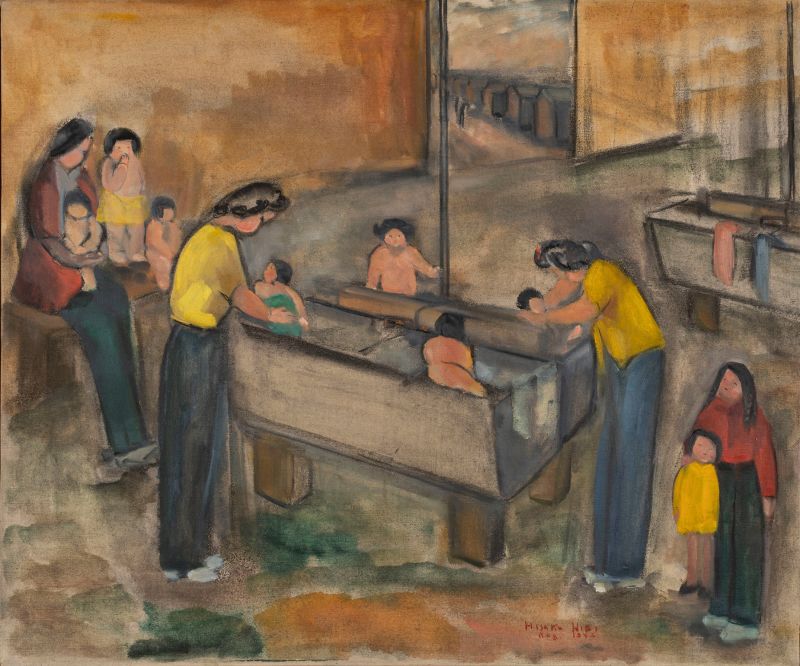

The art covers a wide array of mediums, including oil paintings and pen drawings. The themes explored are equally varied, capturing ordinary moments ranging from women washing clothes in open troughs to men passing the time with a game of cards. Many of the artworks portray individuals carrying on with their daily lives as best as they can.

Other pieces provide a glimpse into the internal lives and personal struggles of those in captivity. Renowned artist Hisako Hibi, who migrated to the United States as a child before being imprisoned in California and Utah, created several portraits of her children at the camps, including "Study" (pictured at the top), which depicts them seated at desks and writing on paper.

"As a mother with two young children, Hibi was well aware of the hardships faced by these women as she painted and taught painting (at the camps)," Yang remarked. "The fact that Hibi produced over 70 paintings and numerous sketches while raising two children at Topaz (a camp housing thousands of prisoners in Utah) is truly remarkable."

Hisako Hibi's "Laundry Room" depicts everyday life in a Utah prison camp that held thousands of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Courtesy Japanese American National Museum

Yang added that the collections diversity reflects the varied experiences of detaineesperspectives that were overlooked by US officials at the time.

Hibi and her fellow artist Miné Okubo's portrayal of the lives of female prisoners, which included highlighting the lack of privacy in shared bathrooms, sharply contrasts with the government's portrayal of these women as exemplary mothers and camp employees, emphasized Yang.

This extraordinary female painter from Edo Japan was highly sought after for her exceptional ink paintings.

Detainees had varying attitudes towards the war and Roosevelts executive order. According to Fujioka, his grandfather expressed his belief in the United States as the greatest country while being sent to the Jerome War Relocation Center in Arkansas, despite his tears. Fujioka, who serves as the vice chair of JANM, shared this account from his family. With visible emotion, Fujioka also mentioned that many of those who were incarcerated, including his mother, hoped that their cooperation would demonstrate their Americanness to their captors.

However, some detainees resisted the executive order, such as Fred Korematsu, who famously went into hiding before being captured and imprisoned. Korematsu later sued the US government, although the Supreme Court ruled against him in 1944. This decision became infamous but was eventually overturned by the same court in 2018.

In the presence of

, Robert T. Fujioka, the Vice Chair of the Japanese American National Museum, stood next to Henry Sugimoto's painting titled "Fresh Air Break from Fresno to Jerome Camp." This artwork portrays the camp where Fujioka's mother and grandfather were confined.

During their confinement, imprisoned artists diligently recorded their experiences, utilizing whatever resources were at their disposal. Notably, Henry Sugimoto demonstrated exceptional creativity by painting on unconventional mediums such as pillowcases, bedsheets, and canvas mattress covers.

"I believe everyone recognized the necessity of seizing the moment in order to safeguard the reprehensibility of the entire circumstance," expressed Fujioka. "They were fully aware that there would come a point where this would hold significance, and that they were essentially capturing history."

Preserving a legacy

The exhibition's location in the US ambassador's residence was highly symbolic, situated in the very room where General Douglas MacArthur had his historic meeting with Emperor Hirohito following Japan's surrender in 1945. According to Ambassador Rahm Emanuel, the venue was chosen due to the rich historical significance that encompasses both the drawing room and the entire building.

The incarceration of Japanese Americans, according to Emanuel, was a disgraceful segment in the history of the United States. "However, the American narrative involves acknowledging and taking responsibility for that disgrace. Learning from our past is an integral part of democracy and our nation," he further stated.

"The Evacuee," a painting by Tokio Ueyama, is accompanied by an exhibition note that states, "This beautifully depicted domestic scene could easily pass for any location, but it actually represents an American detention camp." Courtesy of the Japanese American National Museum.

JANM President and CEO, Ann Burroughs, explained to CNN during the exhibition that it provided a chance to educate both Japanese and American audiences about the incredibly bleak chapter in their shared history.

Moreover, the artworks emphasize the challenges the incarcerated generation encountered upon their release once the camps were shut down. Numerous individuals had lost their homes and businesses during their imprisonment, leaving them with very little to come back to.

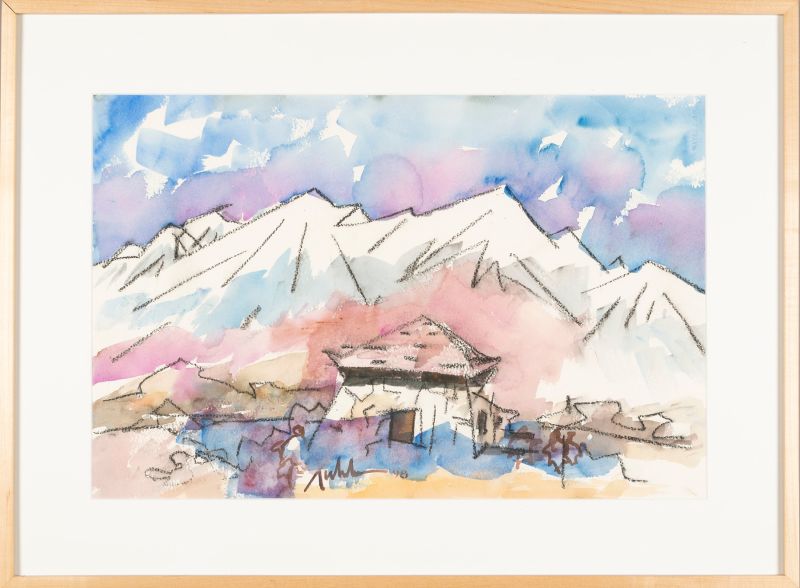

Sugimoto, an artist renowned for his evocative oil paintings, faced extreme poverty when he left the camp, according to Yang. A number of his pre-detention paintings, which he had stored away, were sold in auctions during the war, but Sugimoto did not receive any of the profits. Henry Fukuhara, another detainee, temporarily abandoned his artistic pursuits after his release as his family focused on recovering and establishing a business. It was only in the 1970s that Fukuhara returned to his passion for drawing, painting, and printmaking.

An untitled watercolor produced by artist Henry Fukuhara on the former site of the California camp in which he was incarcerated with his family during World War II.

Providing a prime example is Hibi, who, despite the heavy burden of single-handedly raising her two children following her husband's passing, managed to strike a precarious balance between her job at a garment factory, her passion for painting, and attending art classes. Additionally, many individuals from the group embraced the cause of activism and community service, specifically advocating for reparations.

The exhibited artists and their art "tell you that you can never squash and turn off the human spirit, and theres an act of resilience," Ambassador Emanuel said. "Theres a lesson from that, too."