Unsolved Mystery: The Disappearance of Mallory and Irvine on Everest

In 1924, British climbers George Mallory and Andrew “Sandy” Irvine vanished 800ft below Everest's summit, leaving a century-old mystery. Their fate, and the possibility of reaching the summit, remains unknown. Explore a new theory proposed by a researcher shedding light on this enduring enigma.

One of the biggest mysteries in climbing is whether Mount Everest was first conquered in 1953 or if two climbers reached the summit in 1924 before tragically dying under mysterious circumstances.

British climbers George Mallory and Andrew “Sandy” Irvine were last spotted on June 8, 1924, just 800 feet below the summit, before vanishing into the clouds and never being seen again.

When Mallory’s body was discovered in 1999, there was hope that it would provide insight into whether the pair had made it to the summit. Unfortunately, the camera Mallory carried, which could have shown the highest point they reached, was not found with his body. Irvine's body has still not been located.

However, as the 100th anniversary of the men's disappearance draws near, a researcher claims to have finally unraveled mountaineering's most enduring mystery.

Author Graham Hoyland has studied the expedition weather reports to figure out what happened to the pair and if they reached the summit before they passed away. Hoyland, who is a distant relative of another expedition member and has made nine trips to Everest in search of their remains, believes that air pressure is the key to solving the mystery.

Howard Somervell, a distant relative of his, was also a mountaineer on the same expedition. He came within 1,000 feet of the summit but had to turn back due to lack of oxygen. Somervell was in charge of monitoring the weather during the expedition.

Could this be the key piece of evidence?

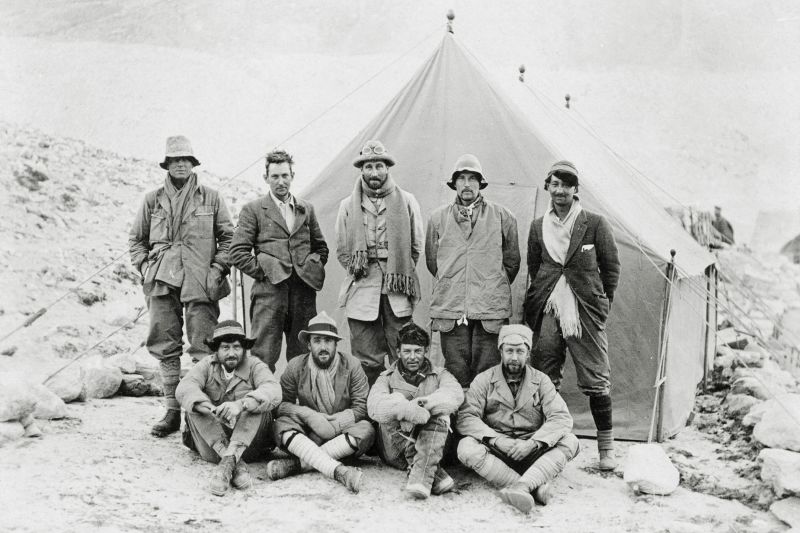

The 1924 expedition, including Irvine and Mallory (top two left), aimed to be the first documented ascent of the mountain.

The 1924 expedition, including Irvine and Mallory (top two left), aimed to be the first documented ascent of the mountain.

J.B. Noel/Royal Geographical Society/Getty Images

After the official report on the 1924 expedition was completed, Somervell, who had returned to his job as a surgeon in India, submitted his records. These records revealed that the barometric pressure had decreased at the base camp between the morning of June 8 and June 9, when Somervell was recording the readings.

Somervell observed the pressure decreasing from 16.25 to 15.98 inches of mercury. Hoyland suggests that this translates to a 10 millibar decrease in pressure. Weather-related deaths on Mount Everest are often linked to a drop in barometric pressure at the summit.

A drop of just 4 millibars can lead to hypoxia, while a 6 millibar decrease caused the tragic event in 1996 where 20 individuals were stranded on the mountain, resulting in the death of eight people. This incident is detailed in Jon Krakauer's book "Into Thin Air." The correlation between bad weather and these events was also explored in a 2010 study by experts from the University of Toronto, led by G.W. Kent Moore.

"They were facing a severe snowstorm, described by Hoyland as a 'snow bomb,' as he shared with CNN. Hoyland himself has encountered such intense storms on Mount Everest. He explained that the experience is terrifying, with a drastic temperature drop and difficulty breathing due to strong winds reaching 1,000 knots. He recounted a story of a person being blown off the mountain and ending up even higher on the mountain.

Due to the decrease in air pressure, the mountain effectively became taller by approximately 650 feet. Hoyland refers to this phenomenon as 'an invisible death trap.'"

This image, captured on May 31, 2021, depicts climbers scaling the Hillary Step as they make their way up the South face to reach the summit of Mount Everest in Nepal.

This photograph taken on May 31, 2021 shows mountaineers climbing the Hillary Step during their ascend of the South face to summit Mount Everest (8,848.86-metre), in Nepal. (Photo by Lakpa SHERPA / AFP) (Photo by LAKPA SHERPA/AFP via Getty Images)

Lakpa Sherpa/AFP/Getty Images

Related article

Why are hundreds of climbers still heading into the 'death zone' on Mount Everest despite the risk of leaving dead bodies behind?

The pair, climbing against the odds along the northwest ridge, faced a daunting challenge. Mallory estimated his chances of reaching the summit at 50 to one in a letter to his wife, while Hoyland believed it was closer to 20 to one. Little did they know what was awaiting them.

In a forthcoming book, it is mentioned that Mallory observed Norton and Somervell coming within 1000 feet of the summit on 4 June without using oxygen equipment. It seemed logical to believe that reaching the top with such gear was possible.

However, what Mallory was unaware of was the fact that the rapidly decreasing air pressure was essentially making the mountain appear even taller.

In addition, the storm and blizzard not only caused a drop in air pressure, but the pair were also dressed in layers of silk, cotton, and wool. Hoyland, who had a custom-made outfit for an Everest trip, mentioned that the clothes were very comfortable but not enough to withstand a blizzard or overnight cold.

It was previously rumored that the pair had reached the summit before their demise on the way back down, which Hoyland dismisses as "wishful thinking."

For years, I had been determined to show that Mallory had reached the summit of Everest before me. I wanted to be known as the 16th Briton to conquer the peak, not the 15th. However, when faced with conflicting facts, I had to accept the truth. I couldn't continue to hold on to wishful thinking," he explains.

Before Hoyland's research, no one had thoroughly examined the weather reports stored at the Royal Geographical Society in London.

The summit was eventually reached by Edmund Hillary, a New Zealand mountaineer, in 1953 – the first documented ascent of the peak.

A century of speculation

Everest is not a mountaineer's mountain anymore, says Hoyland.

Everest is not a mountaineer's mountain anymore, says Hoyland.

Lakpa Sherpa/AFP/Getty Images

The mystery of Mallory and Irvine has intrigued adventurers for decades.

In 1933, a mountaineer named Percy Wyn-Harris discovered an ax near the summit, which was believed to have belonged to Irvine.

In 1936, another mountaineer, Frank Smythe, thought he spotted two bodies in the distance. Through a telescope, he saw them at approximately 8,100 meters, equivalent to 26,575 feet.

Chinese mountaineer Wang Hongbao thought he spotted a body during his climb in 1975.

In 1999, an expedition led by Hoyland discovered Mallory’s body at 26,700 feet, which is 2,335 feet below the summit.

Hoyland suggests that Mallory and Irvine, tied together, fell during their descent from the climb. He believes Mallory may have survived the first fall but tragically fell again while trying to make his way back to base camp. Irvine's body has never been recovered.

According to Hoyland, Mount Everest has a tendency to drive people to madness due to its extreme challenges and dangers.

Whether Mallory and Irvine made it to the top has been one of mountaineering's greatest mysteries.

Whether Mallory and Irvine made it to the top has been one of mountaineering's greatest mysteries.

Gabriel Becker/Alamy Stock Photo

Mallory still had some of his belongings with him when he was found, like a pair of goggles in his pocket. This indicates that he may have been in a dark or poorly visible environment. However, the photo of his wife that he intended to leave at the summit was not found on his body.

Related article

Nepali and British climbers have achieved new records by successfully ascending Everest once again.

For many years, experts have believed that the absence of photos may indicate that the climbers reached the summit but tragically fell during their descent.

After reviewing the new evidence, Hoyland disagrees with the previous belief. According to expedition reports, a blizzard hit the mountain at 2 p.m., much earlier than they could have reached the summit. He points out that the absence of a photo does not hold much weight, as Mallory was known to forget things.

In his final letter to his wife, digitized for the centenary of his climb, Mallory described a bleak scene on May 27. He wrote about looking out of the tent door at a world covered in snow and diminishing hopes, calling it a difficult time. Both Mallory and Irvine were feeling unwell, and Mallory expressed doubts about his fitness.

Hoyland, who is participating in an event at the Royal Geographical Society marking the centenary, believes that "Everest drives people crazy."

According to him, Mallory was consumed by the ambition to summit Everest because he thought it would bring him fame and recognition.

Mallory was a teacher, but he was also connected to the Bloomsbury set, a group of British intellectuals, artists, and thinkers based in London during the early 20th century.

According to him, everyone in his circle was either a renowned novelist or a Nobel Prize winner, which fascinated him and drew him towards the idea of conquering Everest.

Have you ever heard of 'summit fever'? It's when you become so focused on reaching the summit that you are willing to risk everything, even your life. It's like a feeling of 'death or glory', where the only thing that matters is reaching the top.

I can relate to that feeling. Sometimes, the mountain can consume you entirely. Mallory, for example, was so fixated on conquering Everest that it ultimately led to his tragic death.

Hoyland, who now prefers extreme sailing over mountaineering, believes that Everest has turned into a mountain for non-mountaineers.

He expressed his opinion saying, "There are wealthy individuals climbing it as a status symbol. I wish it wasn't the tallest mountain."

“Quite honestly I think the best thing to happen would be if the top 800 feet fell off.

Editor's P/S:

The long-standing mystery surrounding the fate of Mallory and Irvine on Mount Everest has taken a captivating turn with the emergence of new evidence. Author Graham Hoyland's analysis of weather reports reveals a significant decrease in air pressure during the pair's fateful ascent, effectively making the mountain taller and more treacherous. This revelation challenges the previous assumption that the climbers had reached the summit before their demise, as the extreme conditions would have hindered their progress and survival.

Hoyland's research also sheds light on the psychological toll that Everest can take on its climbers. The intense desire for fame and recognition, coupled with the allure of summiting the world's highest peak, can lead to a phenomenon known as "summit fever." This obsession can cloud judgment and push climbers to take excessive risks, ultimately leading to tragedy. Hoyland's own experiences on Everest have given him a profound understanding of the dangers and the psychological lure of the mountain, leading him to conclude that it has become a destination for non-mountaineers seeking status and glory rather than a true test of mountaineering prowess.