Unprecedented 3D Fossil Unveils Extraordinary Evolution of Vertebrate Skulls

Discovering a 455 million-year-old jawless fish fossil with a 3D preserved cranium sheds new light on the evolution of vertebrate skulls, providing valuable insights into the fascinating development of these ancient creatures

Join CNNs Wonder Theory science newsletter to delve into the mysteries of the universe. Stay updated on captivating findings, remarkable scientific progress, and beyond.

Millions of years in the past, Earth's oceans were inhabited by jawless fishes. Their brains were safeguarded by tough skin and cartilage plates. This breakthrough fossil analysis sheds light on the transformation of these ancient fish ancestors into the skulls of modern vertebrates.

Felix Augustin

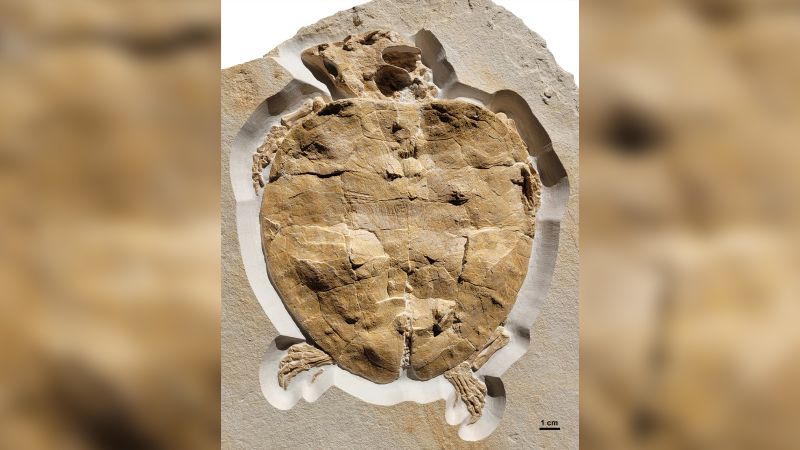

A remarkable fossil of a Jurassic sea turtle has been found, featuring a nearly intact skull and limbs. This well-preserved specimen, estimated to be 455 million years old, belongs to the jawless fish known as Eriptychius americanus. Unearthed in the Harding Sandstone formation in Colorado, this discovery represents the earliest 3D fossil evidence of cranial anatomy in an early vertebrate. The findings were reported in a recent publication in the scientific journal Nature.

Modern descendants of jawless fishes are classified into two groups: vertebrates with jaws, and the jawless hagfish and lampreys. The arrangement of the skull in E. americanus is distinctly different from that of living vertebrates and its extinct fish relatives. It includes unfused cartilage sections, some symmetrical and others not, located at the front of the head. These cartilages surround the mouth, olfactory organs, and eyes. Dr. Richard Dearden, the lead author of the study and a postdoctoral research fellow at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, the Netherlands, describes this unique feature as fascinating.

The late paleontologist Robert Denison, who worked as a curator of fossil fishes at Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History, excavated the fossilized head cartilage in 1949. Describing his findings in 1967, Denison divided the rock that held the fossil material into two parts. In one piece, he used acid to dissolve the rocky matrix and then suspended the fossil in epoxy, according to Dearden.

Denison's analysis uncovered armored scales and cartilage-like structures with distinctive and peculiar shapes. However, further investigation was hindered as dissecting the fossil was necessary, leading to its destruction, according to Dearden.

"The surface details of the fossil are insufficient to provide valuable insights," he clarified. As a result, the specimen was disregarded by the scientific community for many years, deemed intriguing but ultimately impractical for study.

Dearden and his coauthors employed CT scans for the purpose of distinguishing and visualizing the fish's cartilage. According to Dearden, a 3D digital representation of the fish's cranium was created by the team. This research was conducted by Dearden during his time at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom. In an email, he expressed his belief that the reason for the delay in scanning this particular fish is due to the limited number of experts working on Ordovician fishes, and the specialized knowledge required to recognize its significance.

A digital model of the fossil was created from CT scans.

Richard Dearden

Armored and jawless

Ostracoderms, jawless fishes that lived during the Ordovician Period approximately 488.3 million to 443.7 million years ago, were characterized by their armored skin. Fossils of ostracoderms usually only preserve their external armor, leaving little information about the inside of their head. Consequently, researchers have had to rely on the examination of the external armor to make assumptions about the internal structure, such as identifying eye holes as potential locations for eyes in the skull. However, the true nature of what lies inside remains largely unknown.

In the specimen, the study authors discovered a total of 10 cartilage skull pieces - six embedded in the epoxy and four enclosed within the rocky matrix. These pieces were enveloped by scales and possessed canals that potentially housed sensory or vascular structures, as observed in the cartilage.

Significant uncertainties persist regarding the evolution of the skull, particularly concerning the purpose of the canals found in the fossil and the apparent concentration of cartilage at the front of the fish's skull. Dearden suggested that it is plausible that there was additional cartilage at the back of the head, which unfortunately did not survive in this particular specimen.

When jaws first appeared in fish is also still unclear, he added.

Life reconstruction of Fujianvenator prodigiosus with other aquatic and semiaquatic vertebrates from a new Jurassic terrestrial fauna.

Chuang Zhao

A recently discovered dinosaur in China exhibits bird-like characteristics that are both remarkable and unexpected, according to paleobiologist Lauren Sallan. This fossil discovery is seen as significant, as it provides valuable insights into the evolution of vertebrate heads. Sallan, an assistant professor at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University in Japan, noted the importance of this find in enhancing our understanding of this aspect of evolution.

"The scarcity of jawed fish ancestors during the Ordovician period was mainly due to their limited presence in shallow marine environments. Their remains, including Eriptychius, were frequently destroyed by the force of waves after death, resulting in fragmentary fossils," explained Sallan, an expert in marine biodiversity origins who was not involved in the study.

Sallan further emphasized, "Consequently, our fossil collection is quite limited, with very few intact fish heads. Therefore, the discovery of preserved internal structures of these ancient fishes is a significant breakthrough and a significant advancement."