The Bold Impact of Uganda's Fashion Revolution on Second-Hand Clothing

The influx of second-hand clothing from the US and Europe to East Africa has reached overwhelming levels, prompting a need for action Critics are calling for a shift in the conversation surrounding this issue, highlighting the political implications of the second-hand fashion industry

Editors Note: This article is a contribution to CNN Style's ongoing project, "The September Issues: A platform for discussing the influence of fashion on individuals and the environment." It was originally featured on The Business of Fashion, a partner publication of CNN Style.

In 2018, Bobby Kolade, a fashion designer, relocated from Berlin to Kampala, the capital of Uganda, with the goal of establishing a local fashion brand that utilizes Ugandan cotton.

Things didn't go as planned for him. Despite the fact that

, Uganda's textile industry has faced challenges since the 1970s. At that time, there were only two textile mills in the country capable of manufacturing cotton fabrics.

Fast fashion has resulted in an overabundance of inexpensive garments, disproportionately impacting developing nations. This is exemplified by a local market in the Entebbe district of Kampala, Uganda in 2018, as depicted in the following image by Camille Delbos from Art In All of Us via Corbis/Getty Images.

Kolade resorted to utilizing a readily available resource: pre-owned clothing. Within his Kampala studio, he meticulously cleans, disassembles, and reimagines these garments into intricately paneled dresses and creatively patchworked sweats for his Buzigahill brand. As part of his clever "Return to Sender" approach, these designs are then marketed and sold to the very nations that initially discarded them.

This subversive action aims to draw attention to and reclaim a local apparel industry that has been detrimentally impacted by an influx of second-hand clothes and inexpensive imported fabrics from nations such as Turkey and China.

The politics of second-hand fashion

operates on the outskirts of a larger and increasingly contentious global discussion concerning the environmental impact of the fashion industry's waste, and the parties responsible for addressing it.Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni recently unveiled a strategy to prohibit the importation of second-hand clothing into the East African nation. In a speech, he highlighted that this trade hampers the growth of the domestic textile industry. During the inauguration of 16 factories in an industrial park, the President expressed his commitment to promoting African wear by declaring a war on used clothing. The announcement was reported by the Ugandan newspaper Daily Monitor.

Each year, a staggering number of donated T-shirts, jeans, and dresses are transported from collection bins in the United States and Europe to East Africa. This thriving trade contributes to the sustenance of tens of thousands of employment opportunities in both the exporting and importing nations. The second-hand market in the region sustains an entire ecosystem of retailers, cleaners, tailors, upcyclers, and various other interconnected professions.

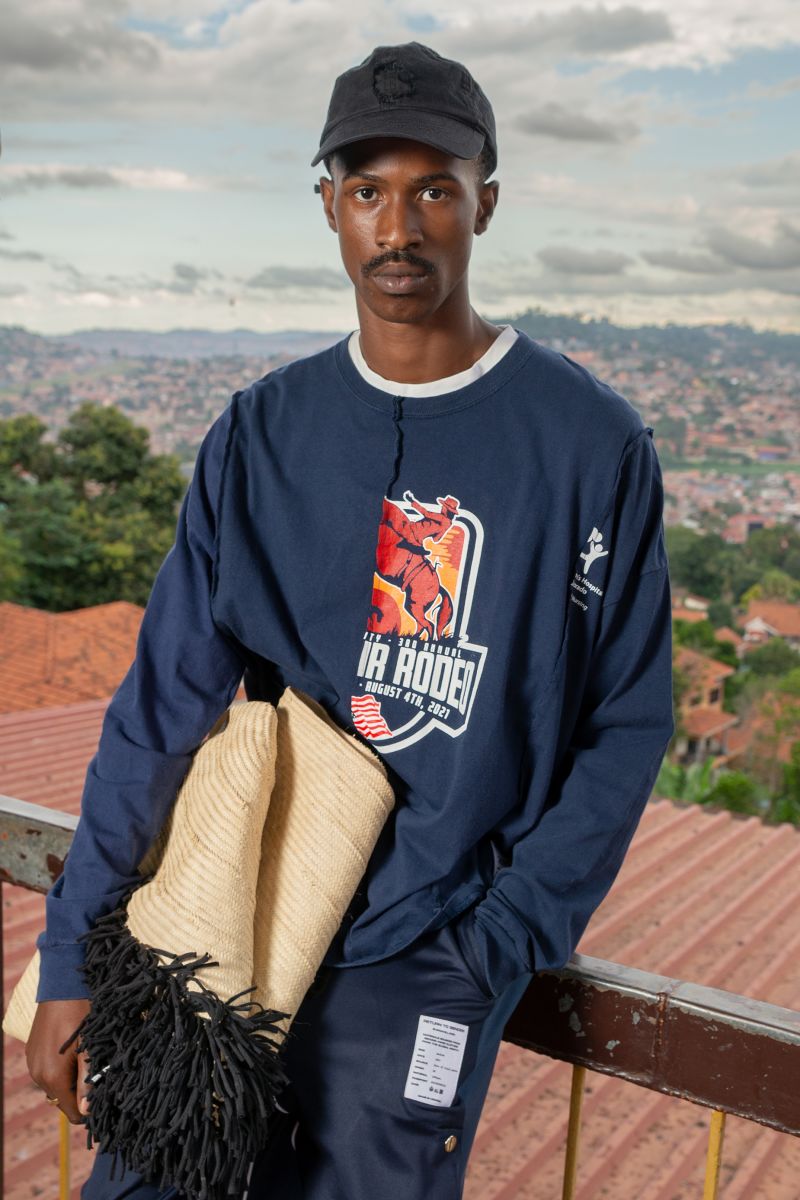

Ugandan fashion house Buzigahill give new life to second-hand clothes through patchworking and splicing pieces together.

Martin Kharumwa

The flow of goods, primarily from countries in the Global North to those in the Global South, has been a source of political controversy for many years. This controversy arises mainly from concerns that it negatively impacts domestic industries. The Philippines, for example, has banned the import of used clothing since 1966, and in the last decade, several other countries, including Indonesia and Rwanda, have implemented similar measures.

Uganda has previously taken steps to regulate this contentious trade. In 2016, the East African Community, a regional economic group composed of seven partner states, including Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Uganda, agreed to completely ban the import of used clothing by 2019. However, under pressure from the US, which threatened to revoke preferential trade terms, only Rwanda followed through with this agreement.

During a phone interview, Corti Paul Lakuma, a research fellow and head of the macroeconomics department at Ugandan think tank The Economic Policy Research Centre, expressed genuine concern about the impact of second-hand clothing on the industrial sector, jobs, and value addition in the region, particularly in the textile industry.

Increasingly, the waste generated by these imports has become a pressing concern, albeit not always addressed in political discourse. The rapid expansion of fast fashion in the past two decades has resulted in a significant influx of unwanted clothing, which environmental organizations such as Greenpeace warn has become overwhelming.

In September 2022, the Kantamanto textile market in Accra, Ghana receives shipments of second-hand garments. Unfortunately, nearly half of these garments are unsuitable for sale and are ultimately discarded in landfill sites.

Exports of used textiles from the European Union have significantly increased, tripling between 2000 and 2019 to reach nearly 1.7 million tons annually, as reported by the European Environment Agency. Africa accounts for almost half of these exports. Unfortunately, the quality and value of the clothing shipped overseas has declined, leading advocates to argue that the second-hand trade now serves as a substitute waste management system. According to The Or Foundation, a nonprofit organization collaborating with the Kantamanto community in Accra, Ghana, approximately 40 percent of the merchandise passing through Kantamanto market, one of the largest secondhand clothing hubs globally, is unsuitable for sale and ultimately ends up in landfills.

Mongolia's steppe is being endangered by the demand for cashmere. Can the industry adopt sustainability measures?

However, prohibiting the trade brings its own set of challenges. The Uganda Dealers in Used Clothing and Shoes Association highlights the numerous jobs directly and indirectly dependent on the second-hand clothing supply chain. Traders would face financial losses if a sudden ban were implemented, as orders are often made well in advance. Additionally, many consumers rely on the affordability of second-hand clothing for their fashion needs. Furthermore, even in the absence of used clothing, domestic industries would find it challenging to compete with inexpensive imports from China.

Changing the conversation

"We oppose a severe and immediate prohibition as the solution to the intricate matter of pre-owned garments," Kolade expressed in an interview. "Only if regional, organic textiles are being utilized, do we show interest in banning the second-hand clothing market to foster the growth of our local industry."The implementation of Uganda's proposed ban is uncertain. According to Lakuma, without a concrete action plan, it is unlikely that anything significant will occur. Kolades' partners are not overly concerned, he added.

Furthermore, should a ban be instituted, enforcing it may pose a challenge. In countries such as the Philippines and Indonesia, where prohibitions have been in effect for years, the trade still persists.

Bobby Kolade, founder of Ugandan label Buzigahill agrees that problems around second-hand clothing are "a complex issue."

Martin Kharumwa

Nonetheless, the move is the latest sign that what happens to old clothes is becoming an increasingly contentious political issue.

The European Union has prioritized addressing fashion waste as a key element of its strategy to promote sustainability in the textile industry. Similarly, California and other states are considering policies that would hold brands accountable for the disposal of clothing at the end of its lifecycle.

This presents an opportunity for discussions on how to establish new industries related to the circular economy in countries that already handle a significant portion of the world's clothing waste. However, Liz Ricketts, the co-founder and executive director of The Or Foundation, expresses concern that prohibitions on second-hand clothing are a diversion that harm existing jobs and fail to address the underlying issue of excessive production driving the trade.

Ricketts claimed that the second-hand clothing trade is dysfunctional due to the already dysfunctional firsthand clothing trade. Consequently, if poor-quality clothing enters the system, it is inevitable that poor-quality clothing will also be produced.