The allure of kohl: Unveiling its ancient origins and modern trends

Kohl, the timeless eyeliner, holds a rich history dating back to ancient Egypt. Beyond its cosmetic use, it served as a shield against the sun and the malevolent 'evil eye.' Explore the fascinating journey of kohl from antiquity to its prominence in contemporary beauty trends.

The use of kohl in the Middle East and North Africa is as diverse as the region itself. Originating in ancient Egypt, eyeliner has been an essential part of Arab culture for thousands of years. It was not only used for beauty but also believed to provide protection against the harsh desert sun and the evil eye, symbolizing a curse or ill-intentioned glance.

Over time, the use of kohl spread throughout the Arabian Peninsula, becoming a daily essential for both men and women. Its versatile applications included aesthetic, medicinal, religious, and practical purposes. There is a belief that Crusaders may have introduced the practice of using kohl to Europe.

The preparation and application of kohl have evolved to showcase the diverse cultural influences of different regions. Traditionally, the pigment is crafted from natural ingredients such as date seeds in Emirati culture, while in Lebanon, cedar honey and even hyena gallbladder have been utilized.

A Palestinian woman Hadeya Qudaih applying traditional kohl eyeliner to her granddaughter in Khan Younis in the southern Gaza Strip in March 2020.

A Palestinian woman Hadeya Qudaih applying traditional kohl eyeliner to her granddaughter in Khan Younis in the southern Gaza Strip in March 2020.

Majdi Fathi/NurPhoto/Getty Images

In rural communities, residents frequently create their own kohl either at home or in communal gatherings. This traditional practice entails gathering easily accessible materials like plants, tree sap, or stone, which are subsequently processed by burning, melting, or grinding into powders using a mortar and pestle. Just like the Ancient Egyptians, Emirati women would also have their kohl interred with them, along with their cherished jewelry and pottery.

Preserving an ancient custom

During Israel’s bombardment of Gaza, my thoughts often drift to Tamam Farhan Abu Issa, a resident of Gaza’s city of Deir al Balah. I first came across her story while conducting research for my book, “Eyeliner: A Cultural History,” which delves into the evolution of cosmetics from ancient times to the present day. In 2022, Abu Issa proudly shared her dedication to preserving the historical tradition of making kohl, using techniques passed down through generations.

Famous American tattooed woman Artoria Gibbons, ca. 1920s. Gibbons was one of the longest-performing tattooed ladies ever. She worked the circus sideshows, dime museums, and carnivals until 1981.

In a video produced by UNESCO, a United Nations agency that collaborates with Palestinian artisans to document and protect traditional crafts, Abu Issa exclaims, “Okay, girls, this kohl, I made it myself!” She emphasizes the significance of this age-old product as a part of the Palestinian people’s rich heritage.

Artoria Gibbons, a famous American tattooed woman from the 1920s, was known as one of the longest-performing tattooed ladies in history. She traveled and performed in circus sideshows, dime museums, and carnivals until 1981. The image of Gibbons is courtesy of the Schiffmacher Tattoo Heritage/TASCHEN.

Abu Issa demonstrates how to make the pigment by soaking a piece of cotton cloth in olive oil and using old robes decorated with tatreez to absorb the excess oil. She then places the cloth under an aluminum pan and allows it to burn above a flame overnight. The process produces soot, which accumulates on the underside of the pan. The superfine powder is collected and stored as kohl in ornate brass pots. Abu Issa dips an applicator moistened with olive oil into the pot to gather the pigment, then smoothly drags it along her lash lines, darkening her eyes.

Hadeya Qudaih makes and sells traditional kohl eyeliner for medical and cosmetic purposes (photograph taken in February 2020).

Hadeya Qudaih makes and sells traditional kohl eyeliner for medical and cosmetic purposes (photograph taken in February 2020).

Amidst the Israel-Hamas conflict, the importance of preserving customs such as kohl-making is highlighted in the Palestinian community. Abu Issa's demonstration of the process not only showcases a traditional method of producing a timeless cosmetic product, but also signifies a strong tie to Palestinian cultural heritage and the region's historical roots. Additionally, this practice serves as a means of perpetuating culture and may even be viewed as a form of cultural defiance.

Kohl, a traditional cosmetic, is utilized in various regions like the deserts of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Palestinian villages during significant events such as weddings, childbirth, and religious festivities. For instance, Abu Issa recalls her grandmother's advice to apply kohl around the newborn's eyes to aid in their sleep, following the belief that it is a Sunnah, or the practice of the Prophet Muhammad, who used a similar form of kohl for medicinal purposes.

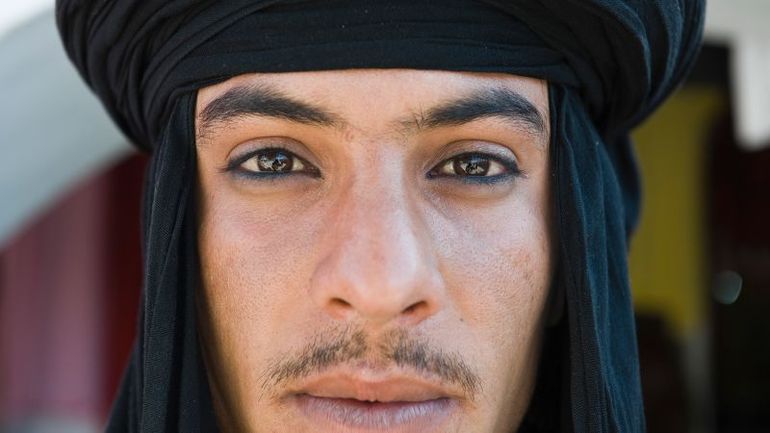

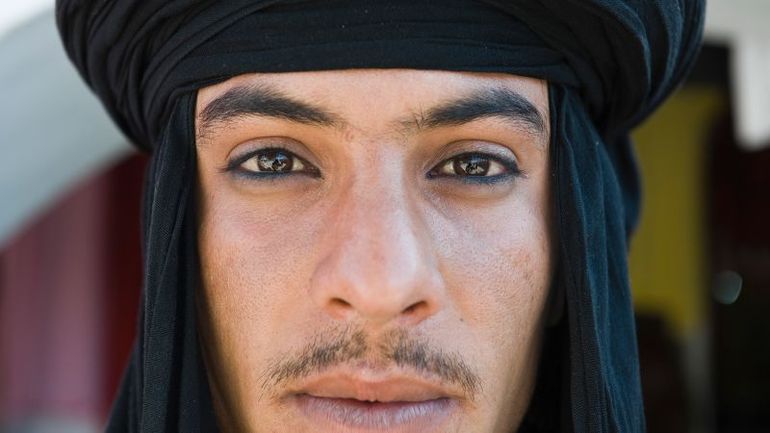

The tradition of applying kohl has its roots in communal practices, particularly among the Bedouin nomads of the Arabian deserts. Kohl is not only used along the waterlines for its beauty, but also around the entire eye area - below the lower lash line and sometimes above the upper lash line. This application serves a dual purpose: enhancing the eye's beauty and offering protection against the sun, wind, and sand. In Saudi Arabia, this reverence for kohl is seen in some men, like the "Flower Men" of the Qahtan tribe, who wear it as a tribute to their tribal heritage.

The internet has been awash with speculation about how Pat McGrath created these ethereal "china doll" makeup looks for the Maison Margiela couture show in Paris.

A Bedouin man wearing traditional kohl, photographed in the ancient Jordanian city of Petra.

Alessandro Bigazzi/Alamy Stock Photo

In Bedouin society, kohl holds significance as a rite of passage into manhood and a symbol of being single. Among the younger Bedouins, there is a playful recognition of the transformative effect of kohl on one's appearance. For example, during an interview in Petra, 19-year-old Bedouin Raed humorously asked, "Do I look like Jack Sparrow, or does Jack Sparrow look like me?" In 2010, the UAE General Authority of Islamic Affairs and Endowments issued a fatwa permitting the use of kohl, as long as it was not for attracting the opposite sex.

Entrenched in cultures

Kohl has proven its resilience over centuries, surviving through wars, colonialism, occupation, the ebb and flow of empires, natural calamities, and major cultural transformations. It has endured economic instability, globalization, and evolving beauty ideals.

A bride paints on kohl at her wedding. Eyeliner has been used for medicinal, cultural and beautification purposes for thousands of years.

The internet has been awash with speculation about how Pat McGrath created these ethereal "china doll" makeup looks for the Maison Margiela couture show in Paris.

Pat McGrath Labs

Legendary makeup artist Pat McGrath is the mastermind behind these now-iconic faces, but the history of eyeliner traces back centuries before it became a staple in Western cosmetics. In Middle Eastern and North African cultures, kohl has long been a revered beauty tradition deeply ingrained in folklore, literature, song, and dance. The captivating allure of kohl-lined eyes is a recurring motif in various Arab art forms, with women often depicted as stunningly beautiful thanks to their "oyoun al sood" or "oyoun kaheela" (black eyes). In fact, the popularity of kohl is so widespread in the region that girls are sometimes named or nicknamed Kahla, meaning "the girl with kohl-rimmed eyes." Beyond mere aesthetics, kohl holds a significant place in ancient myths, rituals, and legends. For instance, Zarqa al-Yamama (Blue Dove), a legendary figure in pre-Islamic folklore, was renowned for her exceptional eyesight attributed to her use of kohl.

Kohl, a traditional cosmetic in the Arab world and Muslim communities, has maintained its popularity but has evolved in its usage. It has become increasingly popular among young women on social media platforms, serving as a bridge between tradition and modernity. Influencers and makeup enthusiasts on Instagram and TikTok often showcase their kohl-lined eyes, with TikTok influencer "Blinkaria Kohl Girl" demonstrating the application process in tutorials that garner millions of likes. Waterlining and tightlining, techniques that involve applying eyeliner to the inner rim of the eyelids and the base of the lashes respectively, have been practiced for centuries and continue to be popular methods for enhancing one's eyes.

A bride paints on kohl at her wedding. Eyeliner has been used for medicinal, cultural and beautification purposes for thousands of years.

Younger generations in urban areas of the Middle East have embraced modern beauty trends such as liquid eyeliner, opting for imported Western or South Asian brands for convenience. Despite the simplicity of making traditional kohl, many women now prefer using ready-made products for ease and cleanliness, as noted by Abu Issa from Gaza. Handmade kohl, however, remains popular among those who value cultural traditions, with some individuals still seeking it out at local souks or from sellers. Maram, an Egyptian woman in her mid-30s, shared in an interview for a book, "I have always viewed kohl as a traditional Egyptian practice. I started using it as a teenager because I found it trendy, and I continue to wear it daily."

Abu Issa, like many others in the Arab world, sees making kohl as more than just a skill; it is a connection to her grandmother's heritage and to her own identity. Despite her grandmother no longer making kohl, Abu Issa is committed to continuing the tradition for herself. She finds joy in creating something that she can personally use and considers it a positive step for self-care.

The book "Eyeliner: A Cultural History" by Zahra Hankir is currently available for purchase in the UK through Harvill Secker and in the US through Penguin Books.

Editor's P/S:

This article transports me to the heart of the Middle Eastern and North African cultures, where the use of kohl has intertwined with history, traditions, and beliefs for centuries. It's fascinating to delve into the diverse applications of kohl, from its aesthetic appeal to its medicinal and protective properties. The resilience and adaptability of this ancient custom is truly remarkable, as it continues to thrive amidst societal changes and global influences.

The article highlights the importance of preserving cultural heritage and the significance of passing down traditional practices like kohl-making. It's inspiring to see individuals like Tamam Farhan Abu Issa dedicate themselves to keeping these customs alive, connecting them to their roots and fostering a sense of identity. The article also emphasizes the transformative power of kohl, not just as a cosmetic but as a symbol of cultural expression and a bridge between generations.