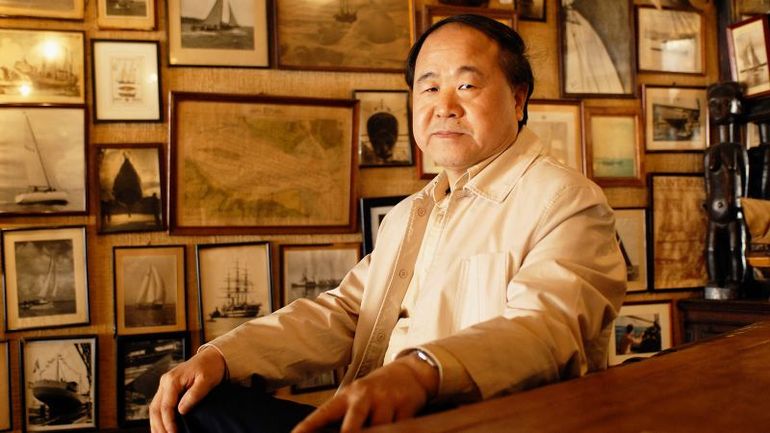

Targeted by Nationalists: China's Former Pride and Nobel Laureate

Just like bloggers and artists, this Nobel laureate is now facing the wrath of China's online nationalists. Explore the story of China's once celebrated figure now under attack by zealous online critics.

Sign up for CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter to learn more about the country’s rise and its impact on the world.

China's online nationalists have targeted bloggers, journalists, artists, comedians, and celebrity chefs. Their latest focus? The country's first officially recognized Nobel laureate.

Mo Yan, a well-known novelist famous for his stories of rural life in China, made his country proud when he became the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2012. A high-ranking Communist Party official congratulated him, saying his win showcased the growth of Chinese literature and the nation's strong presence on the global stage.

However, over ten years later, the 69-year-old writer is facing criticism from a more aggressive form of nationalism that has emerged under Xi Jinping, China's current authoritarian leader.

Under Xi's leadership, the Communist Party has been cracking down on dissenting views, particularly those that do not align with its official narrative on history. This has led to a rise in nationalist commentators who are actively combating any comments deemed as "harmful" to the country's past, especially those that paint the party in a negative light.

One of the prominent figures leading this campaign is Wu Wanzheng, a patriotic blogger known online as "Truth-Telling Mao Xinghuo." For more than a year, Wu has been fiercely criticizing Mo and his novels, accusing them of distorting history and tarnishing the Communist Party's revolutionary history.

Last month, the blogger's campaign gained widespread attention when he announced plans to sue the renowned writer, Guan Moye, for insulting national heroes and martyrs. This is considered a serious crime that could lead to a prison sentence of up to three years, according to a law that was passed in 2018.

In his accusations against Mo, Wu listed numerous alleged wrongdoings found in Mo's books, including the well-known novel "Red Sorghum." This novel tells the tale of love and resistance across three generations of a rural Chinese family during the 20th century, starting from the early years of the war against Japanese invasion.

Wu criticized Mo's portrayal of characters in the Communist army who were unwilling to fight the Japanese and accused him of glorifying Japanese invaders by depicting them as handsome in his book excerpts. Wu expressed his outrage as a patriotic individual, questioning if such behavior should be tolerated in our country.

Wu asked Mo to apologize and give 1 yuan ($0.14) to every Chinese citizen as a way of making up for the situation. He also requested that Mo's books, which he considered controversial, be removed from all stores in China. Wu shared these demands on his Weibo account, where he has gained almost 220,000 followers.

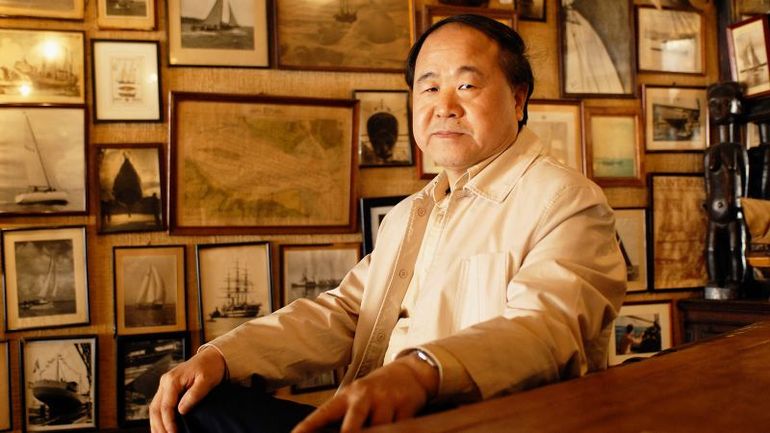

Mo Yan receives the 2012 Nobel Literature Prize from King Carl Gustaf of Sweden during an award ceremony on December 10, 2012 in Stockholm.

Mo Yan receives the 2012 Nobel Literature Prize from King Carl Gustaf of Sweden during an award ceremony on December 10, 2012 in Stockholm.

Jonathan Nackstrand/AFP/Getty Images

‘Chilling effect’

Wu’s attempt to take Mo to court sparked heated debate online on the excesses of nationalism, censorship and the shrinking space for artistic and cultural freedoms.

Many nationalist users supported Wu, while others defended Mo, comparing the attack to the tumultuous Cultural Revolution under Mao, when intellectuals and artists were publicly denounced, humiliated, and beaten by young Red Guards.

According to Zhang Yongsheng, a writer and literature professor at Tongji University in Shanghai, our society has grown more intolerant and filled with taboos over the years, as stated in a social media commentary.

“If I don’t speak up this time, more writers, including myself, could be sued in the future; more professors, including myself, could be convicted for their words.”

A man looks at a painting by Chinese painter Yue Minjun entitled " Hats Series, Armed Forces " during a Sotheby's auction preview in Hong Kong Thursday, April. 2, 2009.

A man looks at a painting by Chinese painter Yue Minjun entitled " Hats Series, Armed Forces "during a Sotheby's auction preview in Hong Kong Thursday, April. 2, 2009.

Vincent Yu/AP

Related article

China’s military has become an untouchable nationalist symbol. Artists and comedians are finding out the hard way

Even Hu Xijin, the former editor-in-chief of the hardline tabloid Global Times, expressed concern about the nationalist reaction. He accused Wu of distorting the words of the Nobel laureate and creating a publicity stunt. (Wu has responded by promising to sue Hu.)

Amid the controversy, Mo, whose pen name is "don't speak," has chosen to remain silent in public. Chinese authorities and state media have also opted not to comment on the situation.

Many people are curious to see how the government will respond. Wu's attempt to sue Mo in a civilian court in Beijing was turned down due to lack of information. Instead, the blogger is now considering filing a public interest lawsuit.

According to Murong Xuecun, a well-known Chinese writer living in exile, Xi's crackdown on free speech has created a "chilling effect" that has led to the increased attacks against Mo.

Xi has been promoting the elimination of opposing opinions. In this political climate, nationalist bloggers frequently search for targets to criticize in order to demonstrate their allegiance to Xi's government. This situation creates a delicate balancing act for those who wish to express dissenting views.

Growing up in rural Shandong province, Mo was born into a farming family and experienced poverty, hunger, and the challenges of the Mao era. He left primary school during the Cultural Revolution and spent his teenage years working on farms. At 21, he joined the army and later began writing fiction while serving as a military officer.

Mo's novels typically take place in modern China, covering events such as the Japanese invasion, the Great Famine, and the Cultural Revolution. Infused with fantasy, satire, and a dark sense of humor, his stories portray the struggles, suffering, and resilience of ordinary people, while also addressing the brutality, greed, and corruption within Communist rule.

In a speech in Hong Kong in 2005, he emphasized that literature should not be used to praise, but rather to uncover darkness and expose social injustices, including the darker aspects of human nature and the nature of evil.

Although some of his writings may have appeared to push the boundaries set by the government, most of Mo's works, written during a time of increased freedom of expression in China, managed to navigate past censors successfully. In fact, some of his works even received prestigious literary awards within the country.

In public, Mo skillfully navigated his words to avoid causing any offense to the authorities. He was appointed as the vice chairman of the state-run Chinese Writers Association in 2011, a position that required approval from the party.

Fried Rice - stock photo

Fried Rice - stock photo

Ray Kachatorian/Stone RF/Getty Images

Related article

Chinese celebrity chef vows to never cook egg fried rice again after nationalist backlash

After Mo won the Nobel Prize, his relationship with the Chinese government became a topic of controversy. Some people criticized him for not speaking out in support of fellow Chinese Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo, who was imprisoned and later died. Others questioned whether Mo deserved the Literature Prize, as it is usually awarded to writers who actively oppose political oppression.

While the Nobel Prize brought Mo international fame, it also led to increased scrutiny within China. Over the years, Mo, who once prided himself on his honesty, has started aligning more closely with the government's views in his public speeches.

In 2013, after Xi took office, Mo passionately defended Chairman Mao, saying that those who tried to criticize him were like "earthworms trying to shake a big tree."

In 2016, at a Chinese Writers Association meeting, Mo praised Xi, calling him "a great person, well-read, with a high appreciation of art, and a true expert."

He told his fellow writers who had gathered in Beijing from across the country that General Secretary Xi is our reader, our friend, and – of course – our ideological guide.

Murong, the exiled writer, doubts that Mo was speaking his true thoughts.

"He said that Mo has chosen these survival skills to adapt to the (political) environment,"

However, despite Mo's enthusiastic praises, he was still vulnerable to nationalist attacks.

In 2022, Sima Nan, a nationalist pundit who is known for his provocative criticism of the United States, made headlines by claiming that Mo's Nobel Prize win was part of a Western campaign to tarnish China's reputation.

In response to this accusation, Murong expressed concern by stating, "This situation highlights the deteriorating state of free speech. It is likely that more writers will start to feel that their safety is at risk."

Editor's P/S:

The article