Steve: The Enigmatic Beauty of Purple and Green Lights

Discover the mesmerizing phenomenon of Steve, not your typical auroras! Uncover its secrets through the lens of citizen photographers Get ready for more sightings as the solar maximum approaches Become a citizen scientist and join the quest!

Subscribe to CNN's Wonder Theory science newsletter and discover the latest news on captivating discoveries, scientific progress, and more that explores the universe.

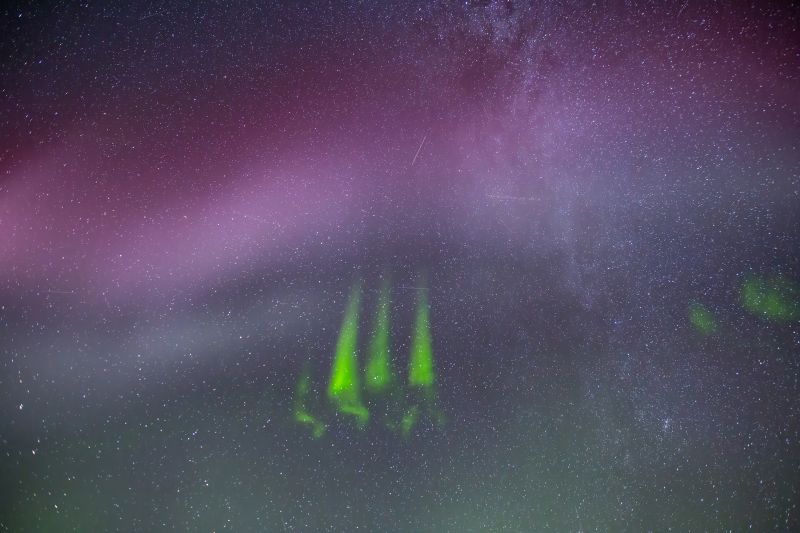

The Northern Hemisphere can experience breathtaking purple and green lights hovering over the horizon. While it resembles an aurora, this phenomenon is actually known as Steve.

This year, the rare light spectacle has been generating a lot of excitement as the sun enters its most active phase, resulting in an increase in stunning natural phenomena in the night sky. People have reported seeing Steve in locations where it is not usually spotted, including parts of the United Kingdom.

However, about eight years ago, when Elizabeth MacDonald, a space physicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, was in Calgary, Alberta for a seminar, she had never witnessed the phenomenon herself. At that time, Steve did not have a name.

Few scientists studying auroras and other night-sky phenomena had ever seen a Steve, which is distinct from auroras in its closer proximity to the equator and its purple-pink arch with green, vertical stripes. MacDonald met with citizen scientists, mainly photographers, after giving a talk at a nearby university, where they shared their passion for capturing the captivating colors of the Canadian sky at Kilkenny Irish Pub.

MacDonald had already been contacting the small local Alberta aurora chasers Facebook group, which was very eager to share their observations and interact with NASA. The photographers arrived with their photos in hand, eager to display the mysterious light show they had captured.

The purple-pink streak of light indicative of Steve is shown in this image captured by Canadian photographer Neil Zeller.

Courtesy Neil Zeller

Naming the spectacle

"We didn't have a precise understanding of the phenomenon," MacDonald commented on the images. Neil Zeller, a citizen scientist or photography expert specializing in aurora chasing, was also present at the meeting.

"I first noticed what was referred to as a proton arc in 2015," Zeller explained. "It had been captured in photographs before but was misidentified. At the meeting in Kilkenny Pub, we had a debate about whether I had truly seen a proton arc."

Dr. Eric Donovan, a professor at the University of Calgary who was also present at the pub that day, contradicted Zeller's claim, stating that what he had seen did not align with the characteristics of a proton arc as described in a paper he co-authored. According to Donovan, a proton arc is "subvisual, broad, and diffuse," while what Zeller saw was "visually bright, narrow, and structured."

The Southern Lights, also called the Aurora Australis, shimmer on the horizon above the serene waters of Lake Ellesmere, located on the outskirts of Christchurch on April 24, 2023. (Photo by Sanka VIDANAGAMA / AFP) (Photo by SANKA VIDANAGAMA/AFP via Getty Images)

Sanka Vidanagama/AFP/Getty Images

Why the northern and southern lights appear to be so active right now

"The conclusion of the evening was inconclusive," Zeller stated. "But let's ensure we no longer refer to it as a proton arc."

Shortly after the pub meeting, another aurora chaser, Chris Ratzlaff, proposed a name for the enigmatic lights on the group's Facebook page.

The group members were trying to gain a better understanding of the phenomenon, but Ratzlaff suggested in a February 2016 Facebook post, "I suggest we refer to it as Steve for now." The name was taken from "Over the Hedge," a 2006 DreamWorks animated film where a group of animals nicknames a towering leafy bush Steve to reduce their fear.

The name persisted, even as the phenomenon became more understood and explanations for Steve began to appear in scientific papers. Scientists eventually created an acronym to accompany the name: Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement.

The meeting at a cozy Canadian pub marked a pivotal moment.

"It was the face-to-face gathering that helped propel us towards gathering increasingly rigorous observations, which we could then correlate with our satellite data," MacDonald explained.

What is Steve?

According to MacDonald, a satellite was finally able to directly observe a Steve, collecting important data. This led to a 2018 study that proposed the lights are a visible representation of a phenomenon known as subauroral ion drift, or SAID.

SAID is a narrow flow of charged particles in Earth's upper atmosphere. While researchers were aware of its existence, they were not previously aware that it might be visible on occasion.

Distinct from auroras, which are illuminated by electrically charged particles interacting with the atmosphere and manifesting as dancing ribbons of green, blue, or red, Steve, if it is caused by SAID, is composed of mostly the same materials. However, it is visible at lower latitudes, appearing as a streak of mauve-colored light accompanied by distinct green bands often described as a picket fence.

Steve can be elusive, often appearing infrequently alongside auroras. Donna Lach, a photographer from Manitoba, Canada, has noted that spotting Steve is often a matter of luck. Despite this, Lach has managed to see and photograph Steve approximately twenty-four times, a feat that is quite rare in the world of sky photography. She attributes her success to her family farm, which is located in a remote area of southern Manitoba and experiences minimal light pollution.

Above is an image of Steve captured by Canadian photographer Donna Lach in 2022.

Credit to Donna Lach

Before leaving the house, she makes it a habit to check the space weather. She specifically looks for conditions to be no less than a Kp3 index, which measures space weather activity on a scale from Kp0 to Kp9, with higher numbers indicating more intense activity.

Lach noted that the phenomenon begins with the stable auroral red arc (SAR Arca) appearing near the auroral oval.

"As it continues, it can move southward...toward the equatorial side of the aurora and develop into a Steve," Lach explained.

A Steve will always appear alongside an aurora, Lach and Zeller said, but not all auroras include a Steve.

Where and how to see Steve

The Earth is entering a phase of increased solar activity known as solar maximum, which happens roughly every 11 years, according to MacDonald. During this period, viewers can anticipate more stunning light displays in the sky and perhaps even the opportunity to witness a Steve at lower latitudes. MacDonald mentioned that light phenomena have been observed as far south as Wyoming and Utah.

Recent storms have been observed in the US, extending down to Death Valley. In November, the storm was visible as far south as Turkey, Greece, Slovakia, and even in China, which is highly unusual. However, Steve is best viewed through a camera lens.

Zeller and Lach pointed out that at first glance, it might seem like nothing more than a faint airplane contrail in the sky, and therefore could be easily missed.

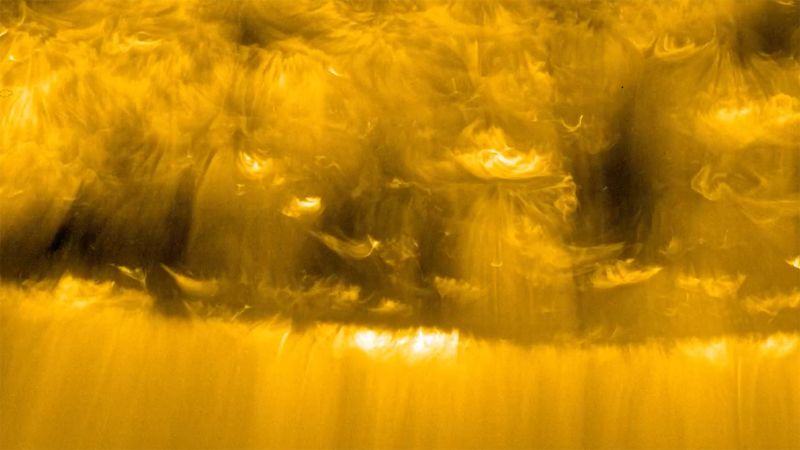

ESA

Solar Orbiter observes jets of material escaping the sun

Cameras are much more sensitive to light, picking up Steves vibrant colors through their lenses.

Even a phone camera can work, MacDonald added.

"This solar maximum is probably the first time that the majority of people's cell phones can capture high quality pictures of the Aurora," she stated.

Zeller and Lach suggest that the Steve phenomenon is most commonly observed around the equinoxes in the spring and fall. (The fall equinox for this year took place on September 23.)

MacDonald pointed out that larger storms of aurora are known to occur more near the equinoxes, and because Steve tends to appear alongside aurora, the phenomenon could be more likely to be observed in March or September. Zeller and Lach noted that they typically see Steve between evening and midnight.

Zeller mentioned that it's not a prolonged event and the longest Steve has seen lasted for an hour. He waits for the auroral storm to start diminishing before turning his camera eastward from his location in Canada or straight up, and then "you start seeing this purple river."

Thats Steve.

How to become a citizen scientist

MacDonald urges those intrigued by photographing auroras or Steve to participate in online communities. She holds a strong interest in Aurorasaurus, a website that links photographers with scientists, emphasizing its significance in aiding scientists in officially identifying Steve. She also emphasized that the public's contributed photos constantly assist scientists in enhancing their comprehension of these stunning light displays.

"Scientists are not as good of aurora chasers as the passionate public," she said. "We dont stay up all night, nor are we photographers."