Revealing the Forgotten Elegance: Vibrant Paintings Adorning the Parthenon Sculptures!

New research reveals that the Parthenon sculptures, long believed to be plain white, were actually adorned with intricate designs and vibrant colors, including the use of Egyptian blue Infrared light has successfully detected traces of the lost paint, shedding light on the original appearance of these ancient masterpieces

Sign up for CNN's Wonder Theory science newsletter to delve into the mysteries of the universe. Stay informed about captivating discoveries, breakthrough scientific advancements, and much more.

According to a recent study, classical Greek marble sculptures, such as the renowned Parthenon sculptures dating back 2,500 years, present a different picture than what we see today. The study reveals that these sculptures were once vibrant and adorned with colorful floral patterns and intricate designs.

Researchers at the British Museum, where almost half of the sculptures are housed, along with Kings College London, have discovered traces of paint on 11 out of 17 figures and a section of frieze on display at the museum. This noninvasive imaging technique was used to identify the paint, as discussed in a recent study published in the journal Antiquity. Dr. Giovanni Verri, the lead author of the study and a conservation scientist at the Art Institute of Chicago (formerly a fellow at the British Museum), explained that paint is rarely preserved on ancient artifacts like the Parthenon sculptures due to prolonged exposure to the elements.

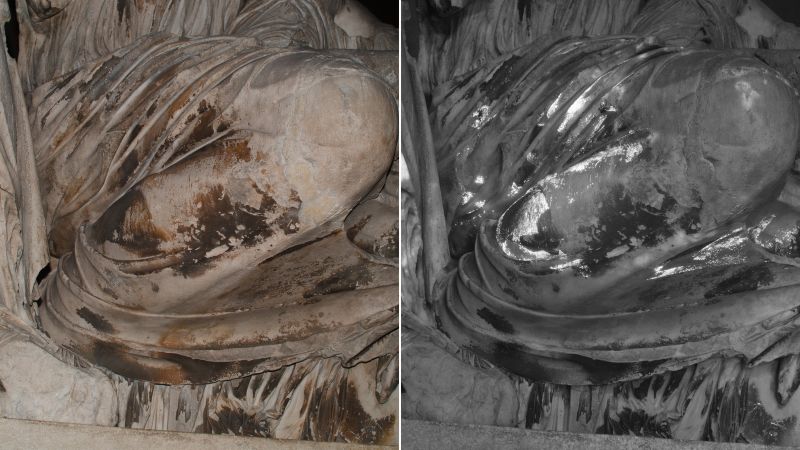

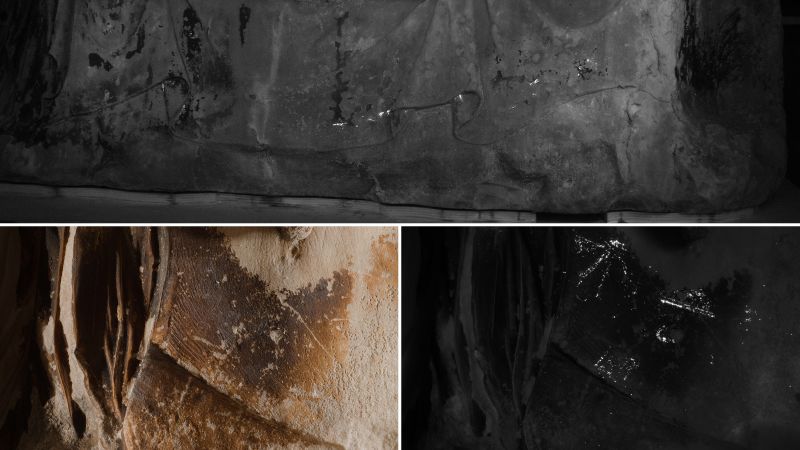

Researchers found microscopic traces of paint by using infrared light that is absorbed by the blue paint and appears on camera as a glowing white (right).

The British Museum's Trustees

"These paint layers are extremely thin and only cover the surface of these objects. They exist at the point where everything happens. They are the first to be affected by the environment," Verri explained. "It is also possible that during conservation or restoration treatments, these small traces, which appeared to be dirt, were unintentionally removed."

Greece has continuously demanded the restitution of the sculptures taken from the grand Parthenon temple in Athens by British diplomat Lord Elgin during his tenure as ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in the early 1800s, at a time when Greece was under Ottoman rule.

Infrared light reveals remnants of vanished paint.

The technique employed in identifying the paint was developed in 2007 by Verri and is referred to as visible-induced luminescence imaging. This process utilizes infrared light to detect minuscule traces of paint that are invisible to the naked eye, as stated by Verri. When the sculptures are illuminated with red light, a pigment called "Egyptian blue" absorbs the light and appears as a luminous white on the camera.

According to the Royal Society of Chemistry, "Egyptian blue" was a popular pigment during its time, created using calcium, copper, and silicon. This vibrant blue hue was highly prized for its rarity and was often reserved for royalty or for representing gods and goddesses.

The researchers found traces of paint on 11 sculptures. Within the statue of Dione and Aphrodite, the forming of flower petals was found (bottom right).

According to the study, the Trustees of the British Museum found the distinct blue color in various parts of the marbles. These include the serpent tail on the sculpture of mythical king Kekrops, the background space of statues Demeter and Persephone, and the garment worn by Dione, mother of Aphrodite. Additionally, two flower petals were discovered near the bottom of the cloth.

Verri explained that the interpretation of these minuscule traces is always intricate. Therefore, they propose these patterns by drawing comparisons with other artworks.

According to Verri, the researchers further observed a purple shade that was not identified through imaging techniques but rather detected by the human eye. The study emphasized that this hue, named "Parthenon purple," is exceptionally distinct as it deviates from the commonly used ancient Mediterranean recipe involving shellfish.

The chair mentioned that the British Museum had about 2,000 items stolen, and efforts are currently being made to recover them. Verri explained that X-ray fluorescence can identify purple color derived from shellfish, but in this situation, that specific color was not detected.

The study revealed that classical texts mention a rare purple color, but the ingredients used to create it were not disclosed due to its high value. "This study provides further evidence of the prevalence of vibrant decoration in ancient Greek art," commented Michael Cosmopoulos, an archaeology and Greek studies professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, who was not involved in the research.

This discovery carries great significance as it challenges the conventional notion that classical art solely comprised of plain white marble. It sheds light on the significance of color in the works of ancient Greek artists. These findings contribute to our understanding of the creative process and the profound meaning behind the Parthenon and its sculptures.

Verri explained that a complete reconstruction of the original appearance of the sculptures is currently unattainable, as the imaging technique only identified the presence of blue paint. Moreover, Verri emphasized that reproducing one of the greatest masterpieces in human history in modern terms is a task that must be approached with utmost care and consideration.

The study revealed no evidence of keying or abrasion on the sculptures, which are usually observed to facilitate the adhesion of paint. Parthenon fragments, previously returned by the Vatican, are now showcased in Greece.

According to William Wootton, a study author from Kings College London, the focus was not just on specific surfaces for paints, but on the integration of carving and color as part of the same objective. The production of sculpture, including both carving and color, was executed with extreme care and attention, which can be seen across the ancient world to a degree that we are still uncovering. The study also highlights previous findings, such as the discovery of colored Greek sculptures in 2008, like the horseman depicted on the West Frieze at the Acropolis Museum in Athens.

Verri said he hopes that further imaging will soon be developed to find other colors present on the sculptures.