Mastering Linux I/O: Unraveling the Mysteries of stdin, stdout, and stderr

Learn how to master stdin, stdout, and stderr in Linux scripts Discover the power of these standard streams that join points, handle data like files, and react to pipes and redirects Redirect and detect both stdout and stderr effortlessly Enhance your understanding of streams within a script

Key Takeaways

Linux commands create three data streams (stdin, stdout, and stderr) that can be used to transfer data about a command

In Linux, stdin is used as the input stream, stdout as the output stream, and stderr as the error stream. This allows redirection of output or errors to various destinations, including files or pipes.

stdin, stdout, and stderr are three essential data streams generated upon executing a Linux command. These streams prove valuable in determining whether your scripts are being piped or redirected. Discover the techniques to utilize them effectively.

Streams Join Two Points

When learning about Linux and Unix-like operating systems, you will inevitably encounter the terms stdin, stdout, and stderr. These three standard streams are created upon execution of a Linux command. In computing, a stream refers to a means of transferring data, and in the case of these streams, the data being transferred is text.

Similar to water streams, data streams have two ends: a source and an outflow. The Linux command you are using provides one end for each stream, while the shell that initiated the command determines the other end. Depending on the command line used to launch the command, this end can be connected to the terminal window, a pipe, or redirected to a file or another command.

The Linux Standard Streams: stdin, stdout, stderr

In Linux, the standard input stream, also known as stdin, is responsible for accepting text input. On the other hand, the standard output stream, referred to as stdout, is utilized for delivering text output from commands to the shell. Furthermore, any error messages generated by the command are transmitted through the standard error stream, commonly known as stderr.

So you can observe that there exist two output streams, namely stdout and stderr, along with one input stream, stdin. Since error messages and regular output are delivered through separate channels to the terminal window, they can be managed autonomously from each other.

Streams Are Handled Like Files

In Linux, streams are treated similar to files. This means that you can read text from a file and write text into a file through streams. Essentially, handling a stream of data as a file is a common practice.

Every file associated with a process is given a unique number, known as the file descriptor. This file descriptor is used to identify the file whenever an action needs to be performed on it.

These values are always used for stdin, stdout, and stderr:

0: stdin

1: stdout

2: stderr

Reacting to Pipes and Redirects

One way to simplify the introduction to a subject is by teaching a basic version of the topic. Take grammar, for instance, where we learn the rule "I before E, except after C." However, it is worth noting that there are actually more instances that break this rule than there are examples that follow it.

When discussing stdin, stdout, and stderr, it is commonly said that a process is not aware or concerned about the destination of its three standard streams. Should a process be concerned about whether its output is directed to a terminal or redirected to a file? Can it discern whether its input is from the keyboard or from another process through a pipe?

In reality, a process does have the ability to know (if it decides to check) and can modify its behavior accordingly if the software developer has implemented that functionality.

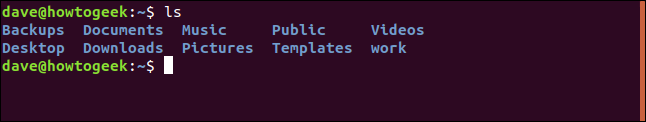

We can see this change in behavior very easily. Try these two commands:

ls

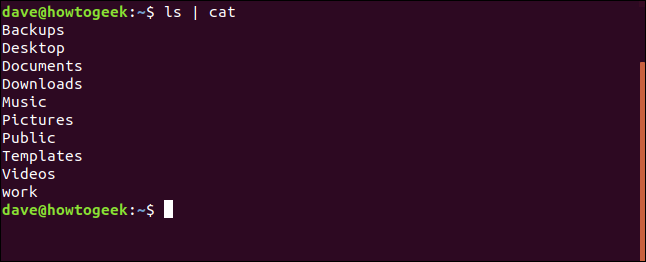

ls | cat

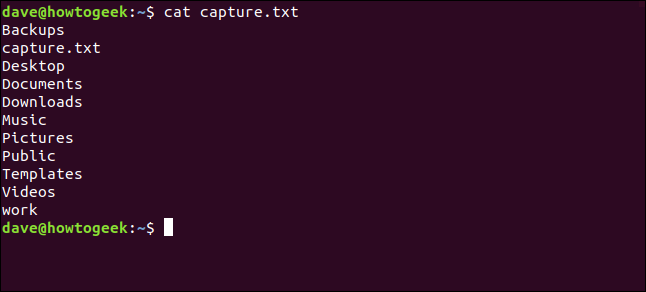

When the output of the ls command is piped into another command or redirected elsewhere, the format of its output changes. It automatically switches to a single column output without requiring any conversion by cat. The same behavior occurs when ls is being redirected.

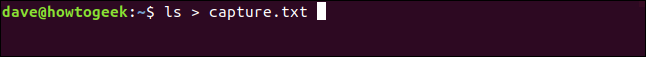

ls > capture.txt

cat capture.txt

Redirecting stdout and stderr

Having error messages delivered through a dedicated stream offers a significant advantage. This allows us to redirect the output of a command (stdout) to a file while still being able to view any error messages (stderr) in the terminal window. It provides the opportunity to react to errors as they happen and prevents the contamination of the file where stdout has been redirected.

Type the following text into an editor and save it to a file called error.sh.

#!/bin/bashecho "About to try to access a file that doesn't exist"cat bad-filename.txt

Make the script executable with this command:

chmod +x error.sh

To run the script, use the following command:

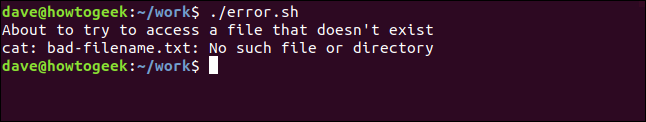

./error.sh

We can see that both streams of output, stdout and stderr, have been displayed in the terminal windows.

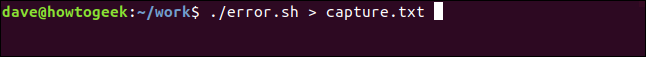

Let's try to redirect the output to a file:

./error.sh > capture.txt

The error message that is delivered via stderr is still sent to the terminal window. We can check the contents of the file to see whether the stdout output went to the file.

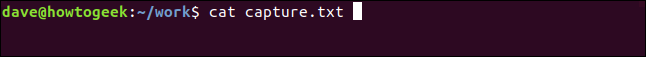

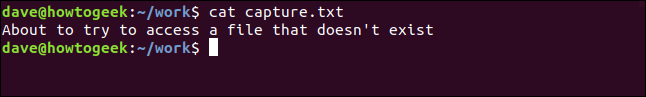

cat capture.txt

The output from stdin was redirected to the file as expected.

To redirect the standard output stream, utilize the following redirection instruction:

1>

To explicitly redirect stderr, use this redirection instruction:

2>

Let's try to our test again, and this time we'll use 2>:

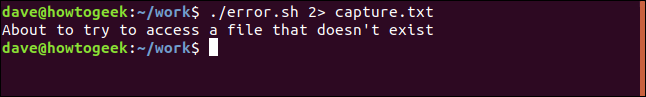

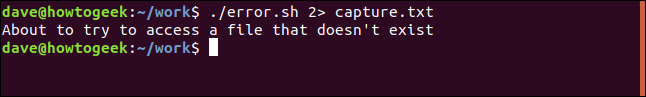

./error.sh 2> capture.txt

The error message is redirected and the stdout echo message is sent to the terminal window:

Let's see what is in the capture.txt file.

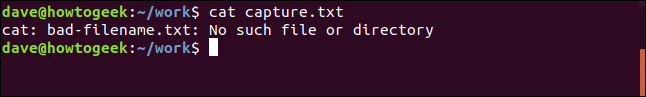

cat capture.txt

The stderr message is in capture.txt as expected.

Redirecting Both stdout and stderr

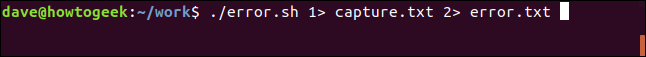

Yes, it is possible to redirect both stdout and stderr simultaneously to different files. For example, by using the following command, stdout will be directed to a file named capture.txt, while stderr will be directed to a file named error.txt.

./error.sh 1> capture.txt 2> error.txt

Because both streams of output, namely standard output and standard error, are redirected to files, the terminal window does not display any visible output. As a result, we are brought back to the command line prompt, giving the impression that nothing has transpired.

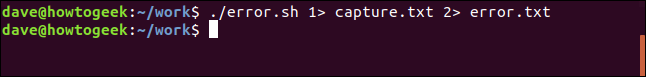

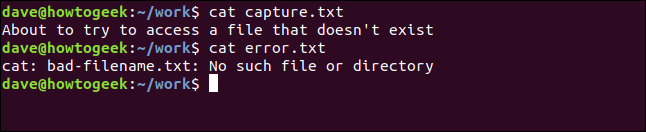

Let's check the contents of each file:

cat capture.txt

cat error.txt

Redirecting stdout and stderr to the Same File

It's impressive how we have managed to allocate separate files for each of the standard output streams. The only remaining option is to direct both the standard output and standard error streams to a single file.

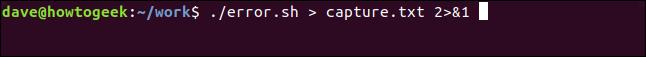

We can achieve this with the following command:

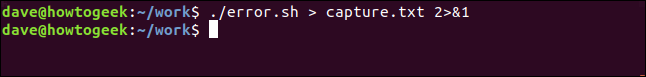

./error.sh > capture.txt 2>&1

Let's break that down.

./error.sh: Launches the error.sh script file.

- Redirects the stdout stream to the file capture.txt using > as shorthand for 1>.

- Implements the redirect instruction &> for stream 2 to go to the same destination as stream 1. This allows stream 2 (stderr) to be redirected to the same location as stream 1 (stdout).

There is no visible output. That's encouraging.

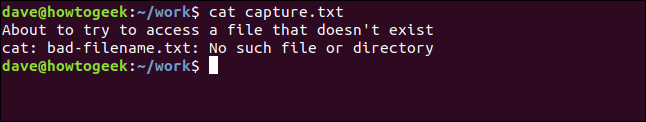

Let's check the capture.txt file and see what's in it.

cat capture.txt

Both the stdout and stderr streams have been redirected to a single destination file.

To have the output of a stream redirected and silently thrown away, direct the output to /dev/null.

Detecting Redirection Within a Script

In our previous discussion, we explored the ability of a command to identify if any streams are being redirected and subsequently modify its behavior. Is it possible for us to achieve the same within our own scripts? Absolutely! This technique is straightforward to grasp and apply.

Type the following text into an editor and save it as input.sh.

#!/bin/bashif [ -t 0 ]; thenecho stdin coming from keyboardelse echo stdin coming from a pipe or a filefi

Use the following command to make it executable:

chmod +x input.sh

The clever part is the test enclosed in square brackets. The -t (terminal) option will yield a result of true (0) if the file associated with the file descriptor terminates in the terminal window. For this test, we have utilized file descriptor 0 as the argument, which represents stdin.

If stdin is linked to a terminal window, the test will return true. However, if stdin is connected to a file or pipe, the test will fail.

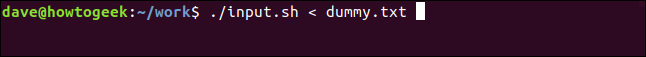

We can use any convenient text file to generate input to the script. Here we're using one called dummy.txt.

./input.sh < dummy.txt

The output indicates that the script identifies that the input is not derived from a keyboard, but rather it originates from a file. If desired, you can adjust the behavior of your script accordingly.

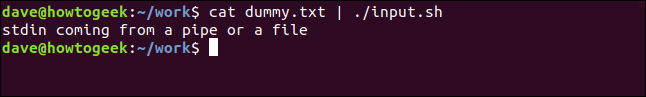

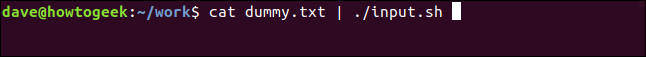

That was with a file redirection, let's try it with a pipe.

cat dummy.txt | ./input.sh

The script recognizes that its input is being piped into it. Or more precisely, it recognizes once more that the stdin stream is not connected to a terminal window.

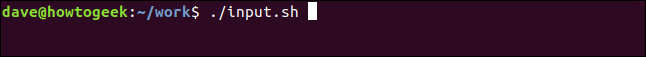

Let's run the script with neither pipes nor redirects.

./input.sh

The stdin stream is connected to the terminal window, and the script reports this accordingly.

To verify the same condition with the output stream, a new script is required. Enter the following code into an editor and save it as output.sh.

#!/bin/bash

if [ -t 1 ]; then

echo "stdout is being sent to the terminal window"

else

echo "stdout is being redirected or piped"

Use the following command to make it executable:

chmod +x input.sh

The test in the square brackets is the only notable modification to this script. For stdout, we are utilizing the digit 1 as the file descriptor.

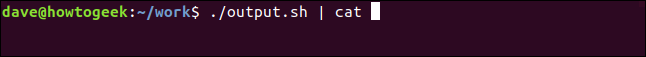

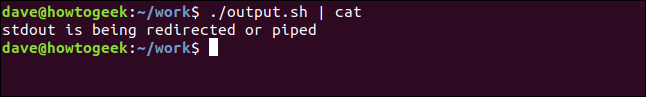

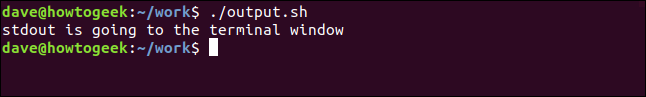

Let's give it a try by piping the output through cat.

./output | cat

The script recognizes that its output is no going directly to a terminal window.

We can also test the script by redirecting the output to a file.

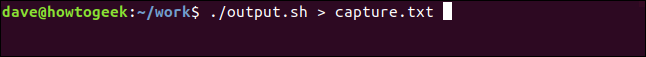

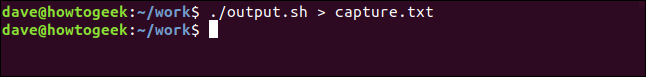

./output.sh > capture.txt

There is no output to the terminal window, we are silently returned to the command prompt. As we'd expect.

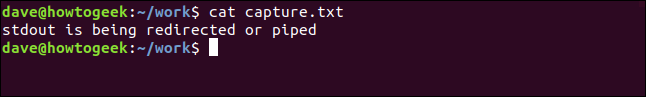

We can look inside the capture.txt file to see what was captured. Use the following command to do so.

cat capture.sh

The simple test in our script once again detects that the stdout stream is not directly sent to a terminal window.

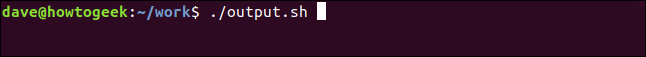

When the script is executed without any pipes or redirections, it should identify that stdout is being directly delivered to the terminal window.

./output.sh

And that's exactly what we see.

Streams Of Consciousness

Knowing how to tell if your scripts are connected to the terminal window, or a pipe, or are being redirected, allows you to adjust their behavior accordingly.

The level of detail in logging and diagnostic output varies based on whether it is destined for the screen or a file. It is possible to log error messages to a separate file from the regular program output.

Typically, increased knowledge results in an increase in available choices.