Indulging in Excess: Ancient Roman Feasting Practices Revealed

Indulge in a captivating journey through the opulent feasts of ancient Romans, where lavish banquets showcased wealth and status Experience their peculiar customs, luxurious comforts, and intriguing superstitions at the table

Picture the most magnificent holiday feast with a giant turkey, two types of stuffing, holiday ham, all the necessary trimmings, and at least six pies and cakes. It may sound impressive, but that is until you compare it to the extravagant ancient Roman banquets.

The wealthy Romans would often take part in extravagant feasts that lasted for hours, showcasing their wealth and status in a way that surpasses our modern ideas of a luxurious meal. "Eating was the ultimate expression of civilization and a celebration of life," said Alberto Jori, a professor of ancient philosophy at the University of Ferrara in Italy.

Ancient Romans enjoyed a variety of sweet and savory dishes. Lagane, a type of short pasta often served with chickpeas, was also used to create a honey cake topped with fresh ricotta cheese. In their cuisine, Romans utilized garum, a strong and salty fermented fish sauce, to add umami flavor to all types of dishes, including desserts. (For reference, garum has a flavor and composition similar to modern-day Asian fish sauces like Vietnam's nuoc mam and Thailand's nam pla.) This highly prized condiment was made by allowing fish meat, blood, and entrails to ferment in containers under the Mediterranean sun.

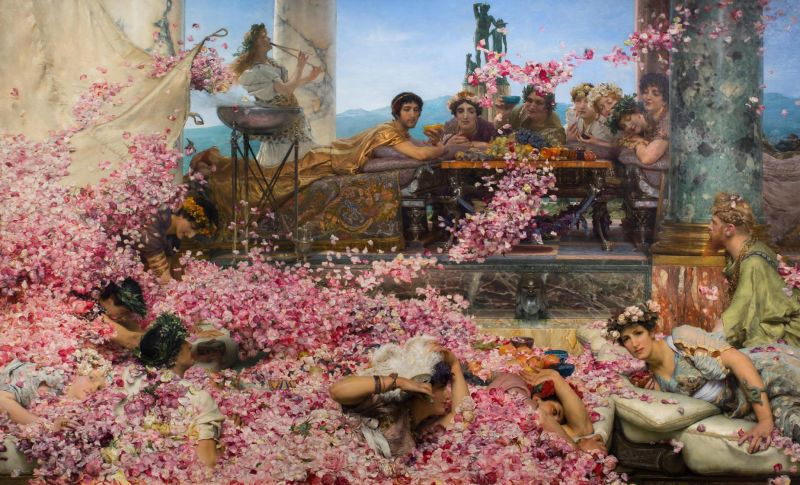

"The Roses of Heliogabalus" by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1888) illustrating celestial Roman diners at a banquet.

Active Museum/Alamy Stock Photo

At the Roman banquet, expensive foods such as venison, wild boar, rabbit, and pheasant, as well as raw oysters, shellfish, and lobster were commonly served. Hosts also competed to serve exotic dishes like parrot tongue stew and stuffed dormouse. "Dormouse was considered a delicacy, as farmers would fatten them up for months in pots before selling them at markets," Jori explained. "And an enormous number of parrots were killed in order to obtain enough tongues to make fricassee."

Giorgio Franchetti, a renowned food historian and expert in ancient Roman history, has unearthed long-lost recipes from these feasts. In his book "Dining With the Ancient Romans," co-authored with "archaeo-cook" Cristina Conte, Franchetti shares these culinary treasures. Together, they offer curated dining experiences at archaeological sites in Italy, allowing guests to savor the opulent dining habits of Roman nobility. These cultural tours also provide insight into the intriguing rituals that accompanied these lavish meals.

One of the intriguing dishes created by Conte is salsum sine salso, attributed to the legendary Roman epicure Marcus Gavius Apicius. This dish was a playful culinary deception designed to surprise and delight guests. A whole fish, complete with head and tail, would be presented, only for diners to discover that the interior was stuffed with cow liver. Such inventive trickery, meant to astound and entertain, played a significant role in the competitive nature of these dining displays.

Bodily functions

Gorging for hours on end also called for what we would consider untoward social behavior in order to accommodate such gluttonous indulgences.

Franchetti mentioned their peculiar dining customs, including reclined eating and vomiting during meals. This ancient mosaic, constructed from shells and coral, was recently unearthed in Rome, dating back 2,300 years.

These practices were part of maintaining a continuous celebration. "Banquets were a symbol of status and often lasted late into the night, with vomiting being a common way to make room for more food in the stomach. The ancient Romans were hedonists, seeking life's pleasures," noted Jori, a renowned author of books on Rome's culinary culture.

It was customary to leave the table to vomit in a room adjacent to the dining hall. Guests would use a feather to tickle the back of their throat and induce regurgitation, Jori explained. Reflecting their high social status, guests, who were exempt from manual labor, would then return to the banquet hall while slaves cleaned up after them.

An engraving of a banquet at the house of Lucius Licinius Lucullus from around 80 B.C.

In Gaius Petronius Arbiter's "The Satyricon," the character Trimalchio exemplifies the social dynamics of Roman society in the mid first century AD. He instructs a slave to bring him a "piss pot" for urination, highlighting the privileged lifestyle where basic needs were catered to by slave labor. This reflects how revelers did not have to go to the bathroom - the bathroom came to them.

The comforts and privilege of wealthy men

It was once considered acceptable to pass gas while eating, as it was believed that holding in gas could lead to death, according to Jori. Emperor Claudius, who ruled from 41 AD to 54 AD, reportedly even decreed the encouragement of flatulence at the dining table, as documented in the "Life of Claudius" by Roman historian Suetonius.

Reclining on a comfortable chaise longue helped reduce bloating and was viewed as the epitome of luxurious living. The horizontal position was thought to aid digestion, a practice believed to be part of the elite lifestyle.

"Romans used to dine while reclining on their stomachs, with one hand supporting their head and the other hand bringing food to their mouths. This allowed for even distribution of body weight and promoted relaxation. Additionally, they would eat with their hands, with the food pre-cut by slaves," explained Jori.

Guests thoughtlessly scattered food leftovers, as well as meat and fish bones, onto the floor. One striking example of this can be seen in a mosaic uncovered at a Roman villa in Aquileia, where the image depicts a scene of scattered fish and remnants of a meal on the floor. The Romans had a penchant for adorning the floors of their banquet halls with such art to disguise the actual food scattered about. This clever use of trompe-l'oeil, known as the "unswept floor" effect, was a sophisticated mosaic technique.

This 2nd century A.D. mosaic depicts an unswept floor after a banquet, to disguise actual mess caused in celebration.

De Agostini/Getty Images

Feast goers could also take the opportunity to relax and even take a short nap in between courses while reclining. However, this privilege was only reserved for men, with women either eating at a separate table or kneeling or sitting beside their husbands.

The Casa dei Casti Amanti in Pompeii is home to an ancient Roman fresco depicting a banquet scene. In the painting, a man reclines while two women kneel on either side of him. One of the women is shown helping the man hold a horn-shaped drinking vessel known as a rhyton. Another fresco from Herculaneum, now at the Naples National Archaeological Museum, shows a woman seated near a reclining man who is also holding a rhyton.

Jori explained that the horizontal eating position of men was seen as a symbol of dominance over women in ancient Rome. It was only later in history that Roman women established the right to eat with their husbands, marking their first social victory against sexual discrimination.

The emperor Nero participating in a bacchanalia, a Roman festival celebrating Bacchus.

Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Superstitions at the table

The Romans were deeply superstitious, believing that anything that fell from the table belonged to the afterworld and shouldn't be retrieved, fearing that the dead would seek revenge. Spilling salt was a bad omen, and bread had to be touched only with the hands. Roosters singing at unusual hours led to servants being sent to fetch, kill, and serve them promptly. Feasting was a way to ward off death, with banquets ending in a binge-drinking ritual where diners discussed death as a reminder to fully live and enjoy life - in short, carpe diem.

According to this belief system, items on the table, like salt and pepper shakers, were crafted in the form of skulls. As Jori tells it, it was tradition to welcome departed loved ones to the feast and offer them generous portions of food. Statues depicting the deceased would sit alongside the living at the table.

A mosaic of a skeleton from the House of Vestals in Pompeii holding jugs of wine

Werner Forman Archive/Shutterstock

Wine was not always consumed straight, but was often mixed with other ingredients. Water was used to dilute the alcohol content, allowing people to consume more, while seawater was added to preserve wine barrels being transported from distant parts of the empire.

"Even tar was frequently mixed with the wine, eventually blending with the alcohol. The Romans could barely taste the unpleasant flavor," Jori explained.

An ancient Roman palace, previously neglected for 50 years, has been reopened to the public.

Legend has it that the epicure Apicius, known for his extravagant banquets, met a tragic end after exhausting his wealth. Despite this, he left behind a culinary legacy, including his renowned Apicius pie, made with a blend of fish and meat, including bird entrails and pig's breasts. However, a dish that might not be as appealing to modern palates.

This article was first published in November 2020.