In 2022, Columbia University Faces Graduation Changes Amid Student Protests

Columbia University is experiencing a pivotal moment akin to the events of 1968, as the decision to cancel the university-wide graduation ceremony sparks controversy amidst student protests regarding Israel's War in Gaza. Learn about the unfolding developments and the parallels to past protests at Columbia.

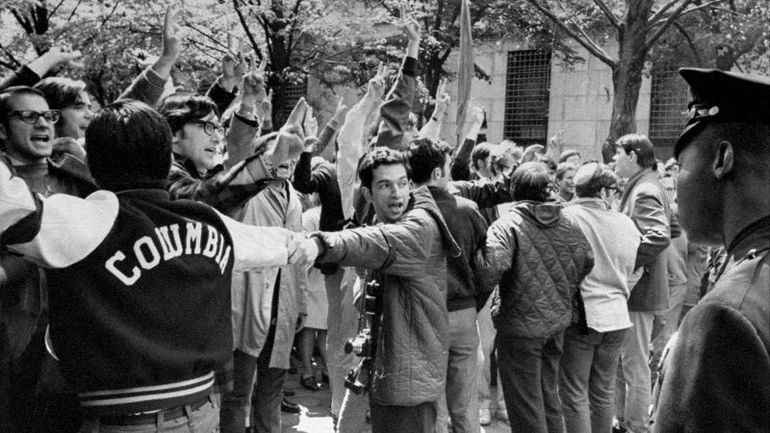

In 1968, Columbia University's graduating class was familiar with protests. The students had been active in the anti-Vietnam War movement and the civil rights struggle throughout their college years.

That spring, tensions escalated after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Events unfolded, leading to a week-long campus strike in April, where students occupied buildings in protest against school administrators.

In the aftermath of the strikes, the then-university president Grayson Kirk decided to relocate the 1968 commencement ceremony from the campus to the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, just a few blocks away.

Now, 56 years later, as spring arrives once again, Columbia faces a similar decision after the administration canceled the university-wide graduation ceremony for the class of 2024. This decision was made in response to student protests regarding Israel's actions against Hamas in Gaza. The direction Columbia takes from this point onward may be influenced by its reflection on past protests.

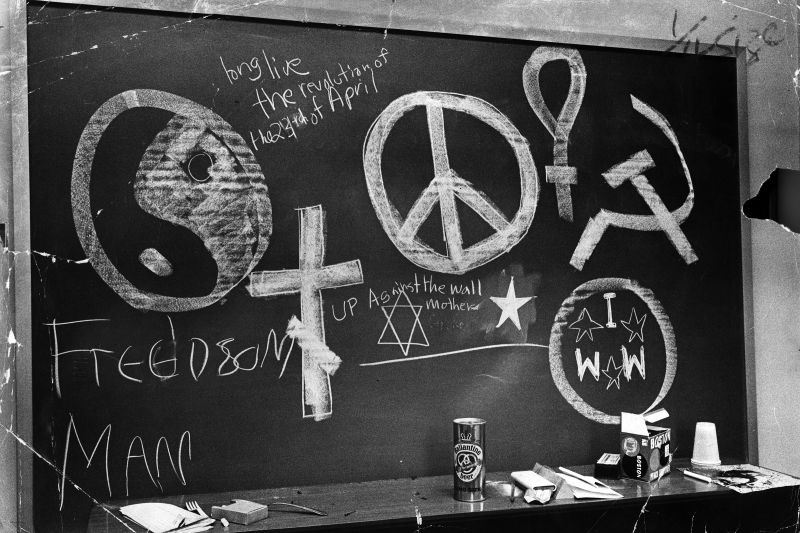

Graffiti on a blackboard at some point after protests began on April 23, 1968 at Columbia University in New York.

Graffiti on a blackboard at some point after protests began on April 23, 1968 at Columbia University in New York.

Neal Boenzi/The New York Times/Redux

When movements collide

Columbia University’s online exhibit “1968: Columbia in Crisis” provides a detailed account of the events that surrounded the controversial commencement ceremony that took place in that year.

Leading up to the graduation ceremony, the campus of the university was engulfed in protests. Various student groups organized demonstrations against what they believed were racist policies and a pro-war stance by the administration.

In April 1967, a disagreement at a US Marine Corps recruitment event caused a chaotic scene with fights and arguments, as reported by the Columbia Spectator. As a result, Kirk decided to prohibit all demonstrations and protests inside campus buildings.

According to the Spectator, students who broke the ban could be subject to disciplinary measures, including potential expulsion. However, this did not stop the increasing sense of disappointment and discontent among the students at Columbia.

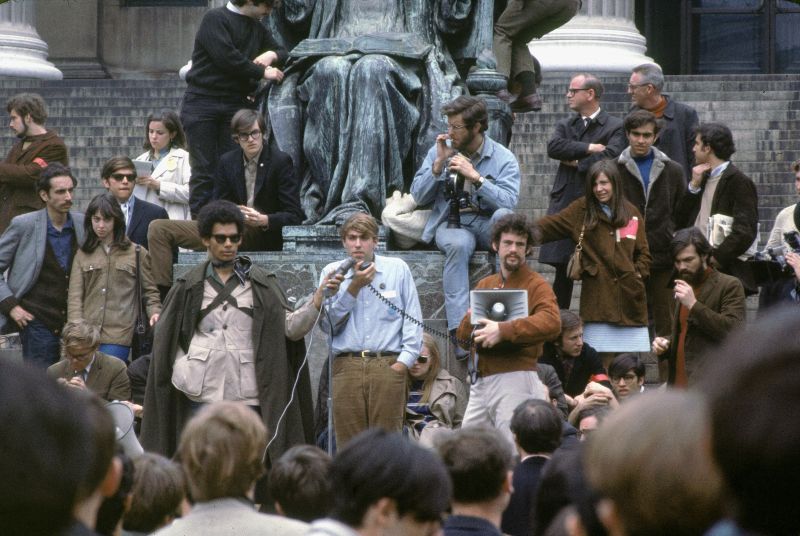

Activist Mark Rudd, center, president of Students for a Democratic Society, addresses students at Columbia University on May 3, 1968.

Activist Mark Rudd, center, president of Students for a Democratic Society, addresses students at Columbia University on May 3, 1968.

In 1968, students and residents of Harlem protested against the university's proposal to construct a gym in Morningside Park. They believed that the unequal access to facilities was a result of racism, as reported by the university archive.

Many students and faculty members were against the university's connection with the military, especially Kirk's position on the board of the Institute for Defense Analyses, a group of universities and government organizations that carry out military research and is still active today.

Tragically, on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.

As the country mourned Dr. King's assassination, the university organized a memorial to honor him. The chairman of Students for a Democratic Society, a student group advocating for progressive causes, accused the administrators of supporting "racist policies" and disrespecting Dr. King's legacy during the service, as reported by the Spectator.

Following his speech, the chairman led a group of students in a walk out, according to the Spectator.

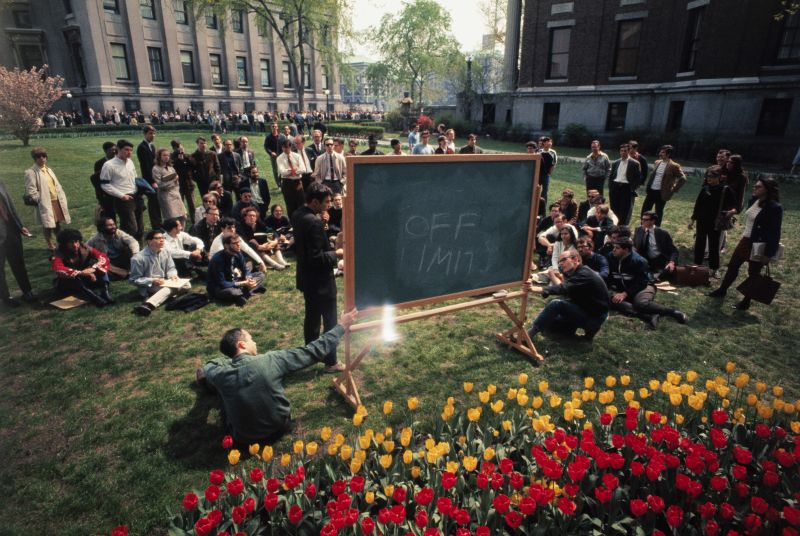

A professor finds an entrance blocked by a student sit-in, at one of four buildings taken over by demonstrations on Columbia University in April 1968.

A professor finds an entrance blocked by a student sit-in, at one of four buildings taken over by demonstrations on Columbia University in April 1968.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Campus implodes as students strike

After Dr. King was killed, students from different campus groups came together to protest against the Morningside gym.

A "Sun Dial Rally" was organized on April 23, where students demonstrated and marched to the gym location. Following this, a sit-in was held at Hamilton Hall, the same building where protesters gathered recently. During the sit-in, students demanded the halt of gym construction and for President Kirk to cut ties with the Institute for Defense Analyses.

The news of the demonstration quickly spread among Columbia's students, leading to more buildings being occupied on campus.

Administrators attempted to negotiate with the student groups to reach a resolution, but the occupation continued for over a week without success.

Police grab a youth as he tries to help a wounded man lying on the ground, after students holding a sit-in at Columbia University buildings were removed on April 30, 1968.

Police grab a youth as he tries to help a wounded man lying on the ground, after students holding a sit-in at Columbia University buildings were removed on April 30, 1968.

AP

Then, in the early hours of April 30, 1968, the administration sent the New York City Police Department to remove students from the buildings on campus.

According to the university's archive, over 700 students were arrested and almost 150 were injured during the campus clearance.

The arrests further fueled the tensions between students and the Columbia administration, leading to the strike continuing for the rest of the semester. The students demanded the resignation of President Kirk and the university's provost.

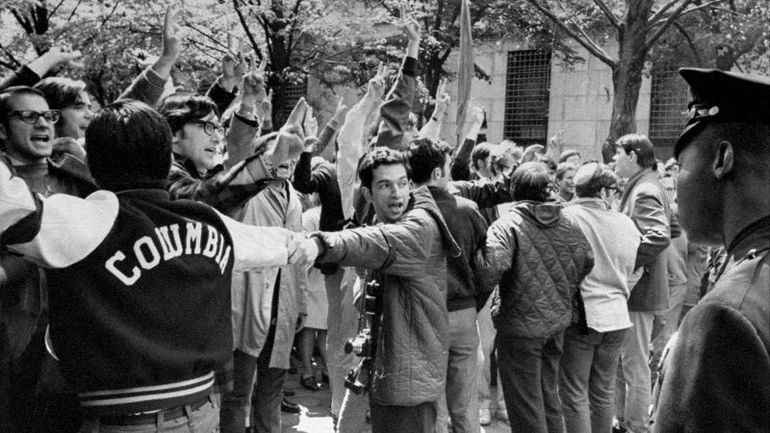

Students backing the Columbia University sit-in clashed with counter-demonstrators outside Low Library on April 29, 1968. The counter-demonstrators blocked access to Low and other occupied buildings, aiming to isolate the demonstrating students from food and prevent others from joining them.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Commencement becomes chaotic

Columbia's class of 1968 graduated on June 4. In a break from tradition, Kirk did not give the commencement address. Instead, history professor Richard Hofstadter spoke at a ceremony near campus.

As Hofstadter started speaking, around 300 graduating students left quietly. They gathered at the university's Low Plaza, where almost 2,000 individuals took part in a counter-commencement event, as documented in the university archive.

The students who stayed to listen to Hofstadter were faced with a thought-provoking question: What type of university do we aspire to become?

At Columbia, we are currently facing a disaster that we cannot fully quantify yet. The extent of our loss is still uncertain as the situation is ongoing and dependent on our actions. Hofstadter emphasized the importance of our response in determining the final outcome.

Professor Stephen Smale of Berkeley, a guest lecturer in Topology and Structural Stability, holds a class in front of Columbia's University's Low Memorial Library. The library, at left rear, and the mathematics building, right, were both held by student demonstrators.

Professor Stephen Smale from Berkeley visits Columbia University to teach a class on Topology and Structural Stability. The class takes place in front of Columbia's University's Low Memorial Library. In the background, you can see the library on the left and the mathematics building on the right. Both buildings were occupied by student demonstrators.

Image source: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

After experiencing a terrible wound, the question arises: How can Columbia move forward? The focus should not be on whether it will continue, but rather in what manner it will do so.

Following the 1968 protests, Columbia University faced a lengthy process of recovery and rebuilding trust between the administration and the student body. Despite the challenges, significant changes emerged as a result.

In March of the next year, Kirk decided to halt the construction of the Morningside Gymnasium after collaborating with Black student leaders, as documented in the university's archive.

During that same spring, there was strong support from students and faculty for establishing a University Senate. This senate, as detailed in the university's records, included faculty, students, and administrators, serving as a platform to discuss and address any issues of University-wide importance.

Editor's P/S:

The article vividly portrays the tumultuous events that unfolded at Columbia University in 1968, highlighting the profound impact of student protests. The parallels between those protests and the current controversy surrounding the cancellation of the 2024 graduation ceremony underscore the enduring tension between authority and dissent within academic institutions.

The administration's decision to relocate the ceremony evokes memories of the 1968 relocation, which was widely seen as a betrayal of student voices. Yet, the 1968 protests also led to significant reforms that fostered greater student involvement in university governance. Columbia's current predicament presents an opportunity to reflect on the lessons learned from the past and to consider how the university can emerge from this crisis with a renewed commitment to academic freedom, dialogue, and student empowerment.