A Marvelous Filmmaker's Take on Alice in Wonderland

Immerse yourself in the enchanting world of Hayao Miyazaki's latest animated masterpiece, The Boy and the Heron This captivating film is a whimsical journey that ignites the imagination, leaving viewers with a profound lesson in embracing limitless possibilities

Noah Berlatsky (@nberlat) is a freelance writer in Chicago. The views expressed here are his own. More opinions can be found on CNN.

The superhero surge in the 21st century has also brought about an explosion of multiverses. Films such as "Into the Spiderverse," "Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness," "Everything Everywhere All At Once," "Spider-Man: No Way Home," "The Flash," and many others are captivated by the potential of endless possibilities. What if you hadn't made that mistake? What if you were bitten by the wrong radioactive spider, or perhaps even by a radioactive cat?

Noah Berlatsky

In various worlds, there may be various villainous alter-egos, but they also offer the opportunity to become someone different, more impressive, and improved. With numerous worlds, anyone - everyone! - can embody their most heroic self. A myriad of possibilities provide each person with ample paths to empowerment.

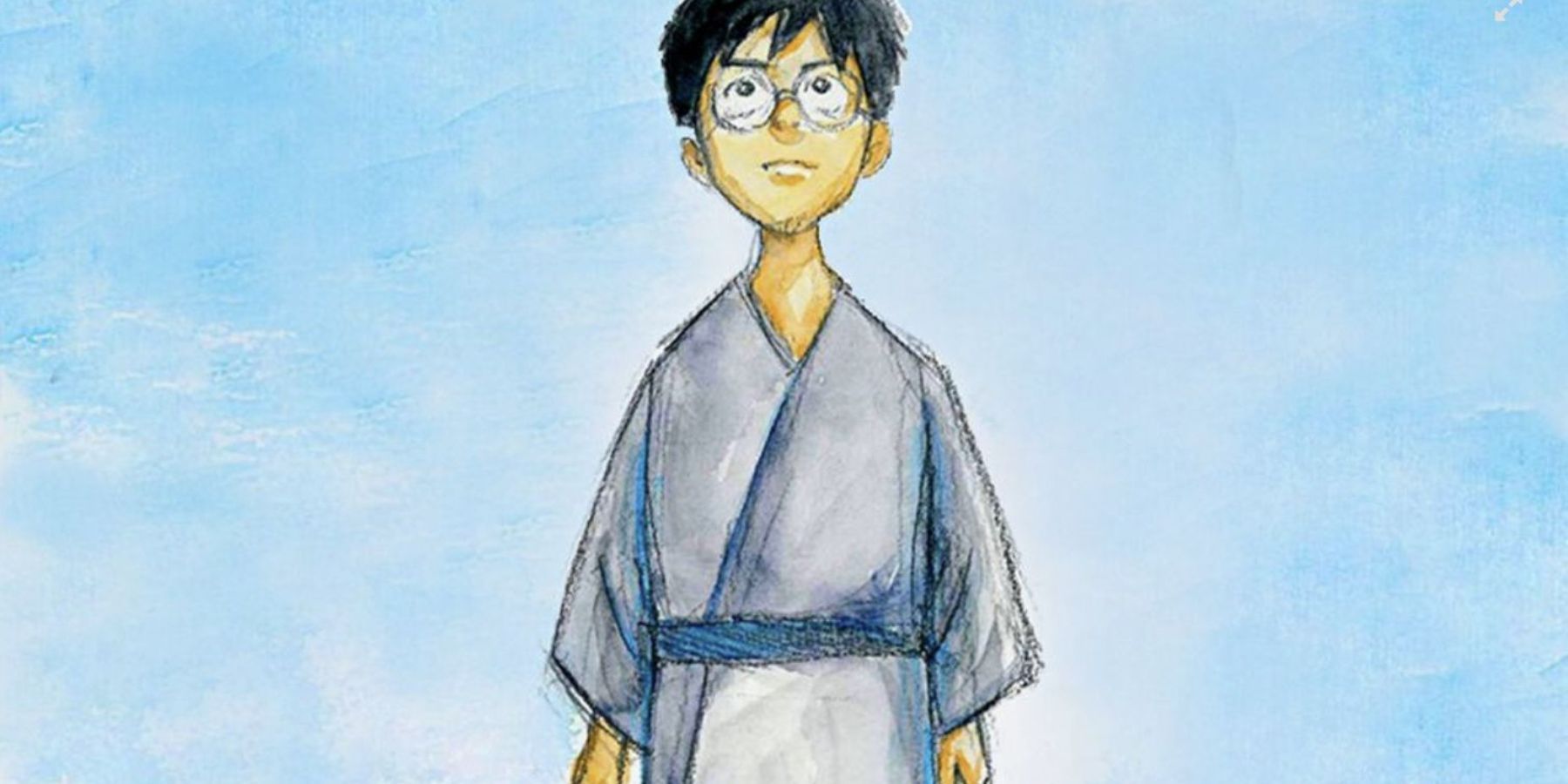

Hayao Miyazaki's latest animated film "The Boy and the Heron" initially appears to follow the empowering multiverse tradition. The story revolves around a young boy named Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki) who embarks on a journey to another world to save his deceased mother.

However, in this case, the alternate reality does not present new possibilities, but rather emphasizes the limitations of the present reality. The contemplation of different outcomes serves as a reminder that the current reality is the only one that exists, much like the reflection in a mirror serves as a reminder of one's true self despite any desire for change. This gives "The Boy and the Heron" a lyrical weight that distinguishes it from even the finest of recent multiverse epics, without necessarily making it a tragedy.

Miyazaki is arguably the most significant Japanese animator of the past 50 years, known for seamlessly blending realistic depictions of the natural world with imaginative characters and scenarios in acclaimed films such as "Princess Mononoke" (1997), "Spirited Away" (2001), and "Howl's Moving Castle" (2004). His work is characterized by a profound sense of tragedy intertwined with a hard-earned optimism about the potential of humanity; Miyazaki's worlds are intricately detailed, enchanting, and tinged with a touch of sadness.

"The Boy and the Heron" follows in the tradition of the director's finest works. The film begins with Mahito's mother, Hisako, perishing in a hospital fire in 1943. The following year, Mahito's father, Shoichi, marries Hisako's sister Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura) and relocates to her rural estate to oversee his munitions factory. Mahito struggles to adapt to his new family dynamic, faces challenges at school, gets into altercations, and even injures himself in the hope of staying home.

"The Boy and the Heron"Â is a hand-drawn, original story written and directed by the Academy Award-winning Hayao Miyazaki.

GKIDS

Mahito becomes more and more annoyed by a gray heron that keeps showing up at his window. Eventually, it exposes teeth, and a big-nosed goblin head inside its beak. It informs him that his presence is required... somewhere.

Somewhere else turns out to be another world where Natsuko disappears and the heron taunts Mahito, urging him to rescue her and Mahito's mother, who the heron claims is still alive. Natsuko follows the bird/goblin to a mysterious tower allegedly built by his great uncle. Upon entering, he emerges in a different world inhabited by giant flesh-eating parakeets. Meanwhile, Mahitos mother's elderly maid Kiriko is a bold young woman sailor who feeds cute round white blob creatures seafood so they can fly into the stars and become babies in Mahitos world.

The other world in "The Boy and the Heron" resembles Alices Wonderland more than Marvel's Earth-41 or Earth-65. The film does not establish a detailed alternative reality with coherent histories and canon, but instead traces the contours of a dream.

A still frame is captured in Academy Award-winning director Hayao Miyazaki's new film.

GKIDS

Mayazaki imbues even the most surreal scenes, such as a large-scale pelican attack, with a sense of hyper-real, inevitable beauty. He also possesses Lewis Carroll's talent for making nonsense adhere to the logic of anxiety. Mahito continuously searches for Natsuko (or his mother?) as the world becomes unhinged and veers off on strange tangents. Why do a series of stacked blocks dictate the world's form? Why is the king of the parakeets negotiating with Mahito's great uncle? What's the deal with the angry stones?

Carroll and Miyazaki both touch on the idea that the alternate world we all experience is the one we enter behind closed eyes each night. Dreams may offer a sense of possibility, but they can also bring feelings of powerlessness, as we lose control over memory, emotions, and time. Dreams do not provide a meaningful escape - when we awake, the real world remains, with all its challenges intact.

For Mahito, his grief remains a constant companion. He harbors resentment towards Natsuko and longs for his mother. The journey to another reality initially seems to offer a chance to right past wrongs, but ultimately it falls short. A poignant moment in the film depicts Mahito reaching out to what he believes is his sleeping mother, only to watch the figure dissolve before his eyes. The new world mirrors the old one, particularly in its eventual unraveling. Despite the many doors, they all lead to the same destination - the other alternate world we encounter, which is death.

Get Our Free Weekly Newsletter

Sign up for CNN Opinions newsletter

Follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Despite its somber tone, "The Boy and the Heron" is a film that delves into themes of failure and loss. However, Miyazaki's work also exudes a sense of optimism. The realization that this world is the only one we have is bittersweet, as it is the same world where Mahito's mother lived and where his sibling will be born. Miyazaki presents the idea that part of the appeal of dreaming about different possibilities is to find a way to live with and within the one possibility we have.

"The Boy and the Heron" does not empower Mahito except in the sense that he learns to accept his own limitations, which is a fate that magic herons, bows and arrows, or a quest cannot truly alter. The multiverse is simply the universe with added regret, denial, and hope - the human "power" of wishing for things to be different. Miyazaki emerges from the heron's throat to tell a comforting lie about there being an escape. However, it is a gentle lie that is also a part of our own world.